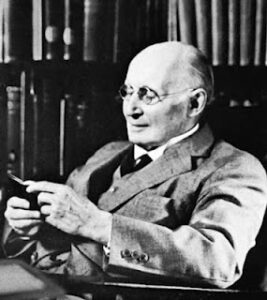

Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) made important contributions in Mathematics, Logic, Philosophy of Science, Metaphysics and in other areas of thought. He was instrumental in developing a philosophical outlook known as “Process Philosophy” of which he is regarded as the founder, though he follows, among others, C. S. Peirce in this regard. Although he began his academic life at Cambridge (as a mathematician), and then taught in London (as a mathematical physicist and philosopher of education), it was in America at Harvard that he became known as a philosopher and wrote his most famous works.

Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) made important contributions in Mathematics, Logic, Philosophy of Science, Metaphysics and in other areas of thought. He was instrumental in developing a philosophical outlook known as “Process Philosophy” of which he is regarded as the founder, though he follows, among others, C. S. Peirce in this regard. Although he began his academic life at Cambridge (as a mathematician), and then taught in London (as a mathematical physicist and philosopher of education), it was in America at Harvard that he became known as a philosopher and wrote his most famous works.

In 1925, he published his Science and the Modern World (1926), a reworking of his Lowell Lectures at Harvard. [1] In 1929, he published his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh as a metaphysical work, Process and Reality. [2] In 1933 he published Adventures of Ideas, his most accessible work and the source of much of what we would call his “political philosophy”. [3] In 1938, he published Modes of Thought, perhaps the clearest summary of his idea. [4]

A few years ago, I picked up an old copy of Science and the Modern World and began to read it again after many years. During those years, I had become a bit more familiar with the meaning and emergence of both relativity theory and quantum theory and the immense difference it made. I was struck by the brilliance of the book. Only fifteen or so years earlier, in 1905 (sometimes called his “miracle year”), Albert Einstein published a series of papers that introduced his theory of relativity and made important contributions to the emergence of quantum physics. This is a short time in the history of science. Yet, Whitehead, himself a mathematical physicist, had internalized the new physics of his day and was able to give a philosophical account of its meaning. It is an account that has continuing relevance today.

End of Materialism

From the time of Newton until the early 20th Century, a fundamentally materialistic world view dominated science and philosophy. In this world view what is “real” is matter and material forces acting upon matter. The picture of the universe that emerged with quantum physics was much different. Matter, atoms and subatomic particles of whatever kind, were not matter. Rather, they appeared to be what Whitehead calls “patterns” or “vibrations” in a universal electromagnetic field, an emerging disturbance in an underlying field of potentiality. [5]

Influenced by developments in physics, Whitehead developed a “process” or “organic” view of reality in which events or what he called “actual occasions” are the fundamental realities. Thus, “Whitehead marks an important turning-point in the history of philosophy because he affirms that, in fact, everything is an event. What we perceive as permanent objects are events; or, better, a multiplicity and a series of events” that have taken up a stable form. [6] Therefore, the actual world is “built up of actual occasions”. [7] Those things that we perceive as stable objects (what Whitehead calls, “Enduring Objects”) are simply events that have an enduring character because of their underlying structure. [8] The vision of the world that Whitehead develops is decidedly not materialistic, for fundamental events are much like the waves that constitute fundamental particles—vibrations or patterns which are capable are not material entities but are capable of becoming so.

A Social World

Early in the development of quantum physics it was realized that one of its implications was a degree of interconnectedness among the fields of activity that make it up. As previously noted, Einstein’s Relativity Theory describes a universe that is deeply relational, in which time and space, ultimate attributes of reality in Newtonian physics, are known to be related to one another and make up a “Space/Time Continuum.” At a quantum level of reality, there is a deep interconnectedness that is revealed and symbolized by so-called, “spooky action at a distance,” or what physicists call, “entanglement.” Reality is deeply connected at a subatomic level. Even at the level of everyday reality, there is a deep interconnectedness that is evident in so-called open systems and their tendency toward self-organizing activity—the so-called “butterfly effect.” [9]

One recurrent emphasis of process thought is on relationships as constituting reality. Actual occasions combine to form societies, and these societies are fundamental aspects of reality. The fundamental character of a society is determined by the relationships in which it is located, past, present, and future. [10] A “society” of whatever character exists within a web of relationships from which it emerged and in a process which is leading to a future state of the process. The relatedness of the universe and the societies that make up the physical realities we experience, according to Whitehead, is not merely external but also internal to the society itself. [11] This not only is physical matter secondary, but also physical power.

A World of Mysterious Interconnectedness

Newtonian physics posited the existence of an observer outside the events being observed. In addition, all connections between particles was external. Quantum physics has revealed that the observer is an irreducible part of the reality being observed. Perhaps more importantly, quantum physics and relativity theory imply a universe of deep interconnection.

The relationship of the observer and the observed is illustrated by the so-called “double slit experiment.” If a researcher shines light through two slits a pattern comes out the other side, which should reveal whether light is a wave or a particle. However, the result is, in some sense determined by the observation we make. It is as if human conscious involvement creates the result and determines the character of the photon and the photon somehow “feels” or senses the observer’s presence.

Process thought shares this view. Human beings are not outside of reality but a part of the “World Process” and even our attempts at abstracting ourselves from that which we observe are at best only partially successful. We are inevitably and inextricably connected to and sense at a deep level the social world of which we are a part. This of true of electrons, but also of our families, neighborhoods, communities, nation, and world. What we say and do has an impact, however important or unimportant on the world we inhabit. These connections are not just external but also intertermal.

A World of Experience “All the Way Down”

Back to the “double slot experiment, it was mentioned earlier the very act of observing — of asking the question, “through which slit will each electron pass?” changes the outcome of the experiment. In other words, the results of the experiment seem to indicate that in some way subatomic particles “know” or “sense” or feel the presence of the observer which determines the outcome of the experiment. In writing his system, Whitehead was well aware of this outcome.

According to Whitehead, every actual occasion has a mental as well as a physical pole. That is to say, that experience and intelligibility are present in everything from subatomic particles to human beings. In Whitehead’s view every level of existence possesses mental and physical poles, including quanta, atoms, cells, organisms, the Earth, the solar system, our galaxy, the universe all the way up to God. For God, the whole physical universe is the physical pole and all of the ideas, the forms, are the mental pole. [12] In other words, there is no ultimate distinction between mind and matter. Mind and matter are two aspects of a single reality. The potential for the kind of consciousness that human beings possess is, thus, an evolutionary possibility within the structure of the kind of universe we inhabit.

There is also no ultimate distinction those societies of actual occasions that are in some sense alive and those (like rocks) that are not, such as between the human race and animals. This can be hard to understand., but refers to the fact that experience and intelligibility go all the way down, and therefore, mind, matter, organic and inorganic matter, humans and animals, for all their differences are also in some sense fundamentally related. This fundamental relatedness and worth has ecological and political implications.

Conclusion

Applied to political philosophy and social theory generally, Whitehead’s process view encourages learners to look at the patterns of relationships that make up the society and polity in which one has an interest—and to look at them as constantly changing events not as an object frozen in time. What we sometimes call the American Experiment in Constitutional democracy is a good example. Our political system is not an object to be dissected and understood solely as the power applied to individuals. Rather, it is an event made up of a complex of constantly changing and evolving relationships. To the extent that our society embraces fundamental values, those values must be continually applied to new and changing realities.

As far as political philosophy is concerned, fundamental “connectedness” implies that our tendency to divide our political world into “us” and “them” is ultimately a false abstraction. We are all part of our families, communities, nation and world, connected in deep ways to those with whom we share all levels of human society. This includes those who disagree with us as well as those who agree, our political allies and our opponents.

Once again, when one combines the process or “event” focus of Whitehead’s thought with its social character, one is led away from any notion of the universe as fundamentally a constituted of matter and force and away from the notion embedded in our culture through Hobbes of society as fundamentally constituted as conglomerations of individuals related to one another by force. Force does exist but it is itself grounded in a deeper reality, which we shall examine next week as we talk about God, Love, and the gradual movement of human societies from force to persuasion.

The existence of a mental pole of reality can be important for political philosophy, as will become more obvious next week. The evolution of the universe and the evolution of human society reflect the propensity of the universe and human society to seek the kind of satisfaction that we call, “Peace” or “Harmony”. Human civilization is the story of the emergence of ideas in the adventure of human knowledge, or the “Adventure of Ideas,” as they impact human knowledge and human society.

Whitehead believed that his metaphysics has practical implications, implications which he outlines in his book, Adventure of Ideas. Next week, we will focus on one idea from Adventure of Ideas—the slow progress of human society from force to persuasion, for from force to love.

Copyright 2022, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York, NY: Free Press, 1925, 1967), hereinafter “SMM”.

[2] Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York, NY: Free Press, 1929, 1957), at 90. Hereinafter, “PR.”

[3] A. N. Whitehead, Adventure of Ideas (New York, NY: Free Press, 1933), hereinafter “AI”.

[4] A. N. Whitehead, Modes of Thought (New York, NY: Free Press, 1938, 1968).

[5] SMM, at 132.

[6] Steven Shaviro, “Deleuze’s Encounter With Whitehead” http://www.shaviro.com/Othertexts/DeleuzeWhitehead.pdf (Downloaded July 18, 2022).

[7] PR, at 96-98.

[8] SMM, 132-133.

[9] This is not the place for a discussion of these phenomena. For those who would like a deeper discussion, see John Polkinghorne, ed, “The Trinity and an Entangled World: Relationality in Physical Science and Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2010). I have examined this phenomena before in a blog entitled, “Politics and the Order of the World” at www.gchristopherscruggs.com (July 8, 2020).

[10] SM, 152.

[11] AI, at 230.

[12] PR, at 128.