The “New Physics,” Process, and Sophio-Agapism

The “New Physics,” Process, and Sophio-Agapism

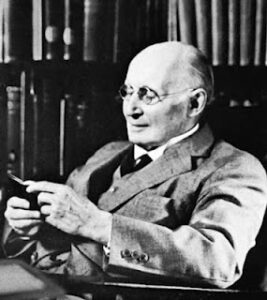

Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) made significant contributions to Mathematics, Logic, Philosophy of Science, Metaphysics, and other areas of thought. He was instrumental in developing a philosophical outlook known as “Process Philosophy,” of which he is regarded as the founder. Although Whitehead began his academic life at Cambridge (as a mathematician) and then taught in London (as a mathematical physicist and philosopher of education), it was in America at Harvard that he became known as a philosopher and wrote his most famous works.

In 1925, Whitehead published Science and the Modern World (1926). [1] In 1929, he published his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh as a metaphysical work, Process and Reality. [2] In 1933, he published Adventures of Ideas, his most accessible work and the source of much of what we would call his “political philosophy.” [3] In 1938, he published Modes of Thought, perhaps the most straightforward summary of his ideas. [4]

Science and the Modern World was published in 1926. Only fifteen or so years earlier, in 1905 (sometimes called his “miracle year”), Albert Einstein published a series of papers that introduced his theory of relativity and made significant contributions to quantum physics. Fifteen years is a short time in the history of science. By this time, Whitehead, himself a mathematical physicist, had internalized the new physics of his day and gave a philosophical account of its meaning. Whitehead’s lasting importance flows from his ability to create a metaphysical system compatible with relativity theory and quantum physics.

End of Materialism

From Newton until the early 20th Century, a fundamentally materialistic worldview dominated science and philosophy. In this worldview, what is “real” is matter and material forces acting upon matter. The picture of the universe that emerged with quantum physics was radically different. Fundamental subatomic particles do not appear to be material. Instead, they seem to be what Whitehead calls “patterns” or “vibrations” in a universal electromagnetic field, an emerging disturbance in an underlying field of potentiality. [5] Whitehead recognized that the implications of developments in physics meant the end of the Newtonian worldview and its materialistic premises.

In response, Whitehead developed a “process” or “organic” view of reality in which the fundamental realities events are what he called “actual occasions.” [6] Those actual occasions that take on a stable form over some period of time, Whitehead sometimes calls “actual entities.” Actual occasions are not fundamentally material but rather a part of a process of becoming. By making the fundamental unity of reality occasions and not particles, Whitehead laid the basis for a non-materialistic metaphysical account of reality.

In defining the fundamental reality as an event or occasion, Whitehead gives metaphysical expression to the fundamental immateriality of what science believes are the basic building blocks of the universe. [7] In so doing, “Whitehead marks an important turning point in the history of philosophy because he affirms that everything is fundamentally an event. What we perceive as permanent objects are events, or, better, a multiplicity and a series of events” that have taken up a stable form. [8] Therefore, the actual world is not fundamentally made up of objects but instead “built up of actual occasions.” [9]

Those things we perceive as stable objects (what Whitehead calls “enduring objects”) are events with an enduring character because of their underlying structure. [10] The vision of the world that Whitehead develops is decidedly not materialistic, for fundamental events are much like the waves that constitute fundamental particles—vibrations or patterns which are capable are not material entities but are capable of becoming so. Higher-order events are built up through structured combinations of actual occasions/objects. In Whitehead’s thought, not only are events primary but so are “structure” or the invisible noetic patterns discernable in actual occasions.

A Social World

Because the notions of pattern and structure are fundamental in Whitehead, the idea of “social order” is basic to his vision of reality. As occasions develop organized and orderly patterns, social order develops, even at a subatomic level. Thus, notions of social and personal order are fundamental because they are the enduring objects or creatures we are familiar with. That is to say, a human being is a society built up of actual occasions. Similarly, everything from rocks to complex social entities or societies of an impersonal type. [11] The development of order over time is a fundamental characteristic of reality, including the existence of human societies.

Early in the development of quantum physics, it was realized that one of its implications was a degree of interconnectedness among the fields of activity that make it up. As previously noted, Einstein’s Relativity Theory, which Whitehead studied and understood, describes a profoundly relational universe in which time and space, ultimate attributes of reality in Newtonian physics, are known to be related to one another and make up a “Space/Time Continuum.” Much of the argument of Science and the Modern World concerns the metaphysical implications of relativity theory, a subject to which Whitehead himself made contributions. In the end, the world that relativity theory describes is fundamentally relational. The absolute space and time of classical Newtonian physics had to give way to a notion of time and space that is fundamentally relational. Time and Space are related and cannot be separated except for purposes of abstract discussion. [12]

At a quantum level of reality, a deep interconnectedness is revealed and symbolized by so-called “spooky action at a distance,” or what physicists call “entanglement.” Reality is deeply connected at a subatomic level. Even at the level of everyday existence, there is a deep interconnectedness that is evident in so-called open systems and their tendency toward self-organizing activity—the so-called “butterfly effect.” [13]

One implication of process thought is based on the idea that relationships constitute reality. Actual occasions combine to form societies, which are fundamental aspects of reality. The essential character of a society is determined by the relationships in which it is located, past, present, and future. [14] A society of whatever character exists as a web of relationships from which it emerged in a process that leads to a future state of the society involved. According to Whitehead, the relatedness of the universe and the societies that make up the physical realities we experience is not merely external but also internal to the society itself. [15] Thus, not only is physical matter secondary, but also physical power.

The notion of reality as a kind of social order has important implications for political thinking. The idea of a society as being built up over time by the gradual unfolding of a social order that is not, at its ultimate basis, material requires a rethinking of any kind of power-based political theory—and casts grave doubt over the exclusion of moral and religious considerations in political decision making.

Humans as a Part of the Process

Newtonian physics posited the existence of an observer outside the events being observed. In addition, all connections between particles were external. Quantum physics has revealed that the observer is a fundamental part of the observed reality. Perhaps more importantly, quantum physics and relativity theory imply a universe of deep interconnection. Reality appears to participate in a profound fundamental, internal unity. As Whitehead puts it,

We awake to find ourselves engaged in process, immersed in satisfactions and dissatisfactions, and actively modifying, either by intensification, or attenuation, or by the introduction of novel purpose. [16]

In other words, all human experience and action, including science, participate in the unfolding process of the universe to which we are inextricably connected.

The relationship of the observer and the observed is illustrated by the so-called “double slit experiment.” If a researcher shines light through two slits, a pattern emerges from the other side, revealing whether light is a wave or a particle. However, the result is, in some sense, determined by our observation. It is as if human conscious involvement creates the effect and defines the character of the photon, and the photon somehow “feels” or senses the observer’s presence.

Process thought shares this view. Human beings are not outside reality but a part of the “World Process,” even our attempts at abstracting ourselves from what we observe are, at best, only partially successful. We are inevitably and inextricably connected to and sense at a deep level the social world of which we are a part. This is true of electrons and also of our families, neighborhoods, communities, nations, and world. What we say and do has an impact, however important or unimportant, on the world we inhabit. These connections are not just external but also internal. As Whitehead[17] puts it, “The whole environment participates in the nature of each of its actual occasions. Thus, each occasion takes its initial form from the nature of its environment.”

A World of Experience “All the Way Down”

One result of quantum physics is the realization that the very act of observing — of asking the question, “Through which slit will each electron pass?” changes the experiment’s outcome. In other words, the experimental results indicate that, in some way, subatomic particles “know,” “sense,” or “feel” the presence of the observer, which determines the outcome of the experiment. [18] Whitehead was well aware of this outcome. In his view, post-modern science implies that experience is a fundamental category of existence. To be is to experience. Even at the most fundamental levels of reality (the level of actual occasions and fundamental particles), a “feeling” or “experience” of reality exists. [19]

Whitehead, of course, understood, but the kind of consciousness that human beings enjoy is not present in fundamental particles, fundamental molecules, fundamental forms of life, and even, perhaps, in some animal life. Nevertheless, there seems to be a form of “feeling” or awareness of connection with surrounding reality at all levels of reality. As the phenomenon of entanglement demonstrates, this awareness of connection may extend to the limits of the universe.

Whitehead uses a technical term, “prehension,” to describe this feeling. [20] It is difficult for human beings to separate consciousness from apprehension. Whitehead, therefore, coined the term “prehension” to describe a form of non-cognitive apprehension as it exists in nature. Prehension is an outgrowth of the fundamental relatedness of reality as each form of existence (actual occasions) “prehends” surrounding reality.

Conscious perception is possible because we have a highly developed central nervous system. But this consciousness is only a tiny part of the considerable amount of consciousness contained in the universe. It would seem that at every level of reality, there is a constantly expanding and more complex form of experience available. All living creatures would seem to have some awareness of their surroundings and of the impacts their surroundings have upon them. In animal life, we see a growing form of awareness. In humans, we see still another form of awareness, but all this “experience” is built upon a kind of awareness or prehension present in the most fundamental aspects of reality.

This world of deep and beautiful order is deep and beautiful on several levels. In some way, the immaterial potentialities of the quantum world emerge, and from the indeterminate world of quantum reality, what we call ordinary reality and the laws of physics emerge. These laws that rule over matter and energy at the most fundamental levels allowed the emergence of what we would call “chemistry,” the basic elements making up the physical universe and their combination, out of which emerged biology, eventually resulting in the emergence of the human race—a race having self-consciousness and the ability to reflect the order of the universe in its relations as well as the ability to create culture, societies, and social structures. From the human race emerge families, society, social organization, law, economic systems, arts, literature, music, morality, religion, and all the myriad of complex social relations that make up any society. [21]

These levels of reality are, in some way, dependent upon each prior level in the emergent hierarchy of reality. Yet, they each possess independent rules, regulations, laws, and order founded on but not identical to the order from which it emerged. Finally, each level of reality participates in an invisible noetic order from which the material order emerges, which itself is emergent, within which various levels of existence have their conceptual order. That is to say, humans can investigate the underlying structure of reality using science and other disciplines. The means of investigation depends on the nature of the order.

This organic, interconnected, and hierarchical view of reality has critical political philosophy and practice implications. Every stable society is built ahead of multiple levels of increasingly complicated participants in the social order. For example, we tend to think that our society is made up of humans who happen to be residents of the United States of America. However, the health and functioning of the society end of the residence depends upon their interconnected participation in the universe that includes all its surrounding physical and non-physical elements.

Not surprisingly, one fundamental application of Whiteheadian philosophy has been in the area of environmental protection. The notion that the world is built up of actual occasions or objects connected by feelings and sense and responds to the existence and presence of one another implies that the members of our society are connected with its environment, human, non-human, organic, organic, and otherwise. If this is true, then it is impossible to have a healthy society that does not consider this web of relationships in which the human participants are located.

A Physical and Mental Universe

One of Whitehead’s contributions to philosophy is how he avoids the mind-body dualism inherent in modern metaphysics. According to Whitehead, every actual occasion has a mental and a physical pole. That is to say, that experience and intelligibility are present in everything from subatomic particles to human beings. In Whitehead’s view, every level of existence possesses mental and physical poles, including quanta, atoms, cells, organisms, the Earth, the solar system, our galaxy, and the universe up to God. For God, the whole physical universe is the physical pole, and all ideas and forms are the mental pole. [22] In other words, there is no ultimate distinction between mind and matter. Mind and matter are two aspects of a single reality. The potential for the kind of consciousness that human beings possess is, thus, an evolutionary possibility within the structure of the type of universe we inhabit. [23]

There is also no ultimate distinction between those actual occasions that are in some sense alive and those (like rocks) that are not or between the human race and animals. As mentioned above, the mental pole does not imply a consciousness. Returning to the double slit experiment, when quantum physicists speak of a particle as “sensing” the observer, they do not mean to imply that subatomic particles are conscious. This can be hard to understand., but it refers to the fact that experience and intelligibility go all the way down, and therefore, mind, matter, organic and inorganic matter, humans and animals, for all their differences, are also in some sense fundamentally related in an intelligible way. [24]

Applied to political philosophy and social theory generally, Whitehead’s process view encourages investigators to look at the patterns of relationships that make up the society and polity in which one is interested—and to look at them as constantly changing events, not as an object frozen in time. What we sometimes call the American Experiment in Constitutional democracy is a good example. Our political system is not an object to be dissected and understood solely as the power applied to individuals. Instead, it is an event that comprises a complex of constantly changing and evolving relationships. To the extent that our society embraces fundamental values, those values must be continually applied to new and changing realities.

As far as political philosophy is concerned, fundamental “connectedness” implies that our tendency to divide our political world into “us” and “them” is ultimately a false abstraction. We are all part of and inevitably connected to our families, communities, nation, and world, joined in profound ways to those with whom we share all levels of human society. This includes those who disagree with us and those who agree, our political allies, and our opponents. This kind of relatedness casts doubt on the viability of any political philosophy that relies solely on power to the exclusion of other relational factors.

Once again, when one combines the process or event focus of Whitehead’s thought with its social character, one is led away from any notion of the universe as fundamentally constituted of matter and force and away from the idea embedded in our culture through Hobbes of society as fundamentally formed as conglomerations of individuals related to one another by force. Power exists, but it is grounded in a deeper reality, which we shall examine next week as we talk about God, Love, and the gradual movement of human societies from force to persuasion.

The evolution of the universe and human society reflects the propensity of the universe and society to seek the kind of satisfaction that we call “Peace” or “Harmony.” Whitehead believes his metaphysics has practical implications, which he outlines in his book Adventure of Ideas. Whitehead’s metaphysics supports a view that sees justice as a kind of harmony within the social process that constitutes a society—a goal that policymakers should seek rather than power or ideological victory in the political sphere.

Eternal Objects

To understand Whitehead’s views on the movement from a society based on force to one based on persuasion, it is crucial to understand his notions of reality, God, and universals, what Whitehead calls “Eternal Objects.” As mentioned above, the world in which we live and have our day-to-day existence (what Whitehead sometimes calls the “Actual World”) is built up over long periods through the emergence and relationships of actual occasions. [25] Those things we perceive as stable objects (what Whitehead calls “Enduring Objects”) are events with an enduring character because of their underlying structure. [26]

For Whitehead, however, two objects participate in the emergence of the world of actual occasions that are not themselves actual occasions. These are:

- Eternal Objects, which are ideal entities that are pure potentials for realization in the actual world and form the conceptual ground for all actual occasions; [27] and

- God is both an Eternal Object and the primordial actual entity; God is not an actual occasion but is present in all occasions. [28]

According to Whitehead, eternal objects are the qualities and formal structures that define actual occasions and related entities. An infinite hierarchy of eternal objects defines each actual entity. This feature permits each real entity to be experienced by future entities in essential ways.

- Eternal objects participate in the causal connection of individual entities, functioning as private qualities and public structures, characterizing the growth of actuality in its rhythmic advance from private, subjective immediacy to public, extensively structured fact.

- Eternal objects are ideals conceptualized by historical actual entities. As such, they are the potential elements that ensure that the process of nature is not deductive succession but organic growth and creative advancement. [29] This characteristic is essential for understanding such political notions as Justice.

Eternal objects are primordially realized as pure potentials in the conceptual nature of that one unique actual entity, which we call “God.” As realized in God, eternal objects are ideal possibilities or potentialities, ordered according to logical and aesthetic principles, which can be realized in actual occasions. As realized in God, Eternal Objects transcend the historical actual entities in which they are realized. [30]

Persuasion Instead of Force

For Whitehead, God is “actual” (an actual entity) but non-temporal and the source of all creativity, the source of innovation who transmits his creativity in freedom and persuasion. [31] Whitehead’s God has two poles of existence: a transcendent pole, which is primordial, and a consequential or physical pole. The transcendent pole is the “mental pole” of God, wherein one finds the existence of eternal objects. As primordial, God is eternal, having no beginning or end, and is the ultimate reason for the universe. [32]

God’s consequential or physical pole implies that God is present in the universe and in all actual occasions, which are the physical poles of God’s existence. In this physical pole, God experiences the world and the actualization of eternal objects in actual occasions. Because of God’s physical pole, God can be impacted by and experience actuality. Thus, Whitehead’s God experiences and grows with creation. Process Philosophy uniquely contributes to philosophical and theological ideas in postulating a physical pole to God.

For Whitehead, God is not an all-powerful ruler, a cosmic despot. God is intimately involved in the universe of Actual Occasions and impacts the future not by force but by persuasion. [33] Thus, he says,

More than two thousand years ago the wisest of men proclaimed that the divine persuasion is the foundation of the order of the world, but that it could only produce such order as amid the brute force of the world it was possible to accomplish. [34]

This divine persuasion, the slow working of God in history as love and wisdom, is the hope of the world that the constant resort to force and violence in human affairs can be overcome. Writing before the Second World War, before Hiroshima, and the wars of the last century, Whitehead saw the critical role of faith and all religious groups as instruments for the evolution of the human race towards a more harmonious world based on persuasion, reason, and love rather than brute force. [35] In a much-quoted and beautiful passage, speaking of Christianity in particular, Whitehead writes:

The essence of Christianity is the appeal to the life of Christ as the revelation of the nature of God and of his agency in the world. The Mother, the Child, and the bare manger: the lowly man, homeless and self-forgetful, with his message of peace, love, and sympathy: the suffering, the agony, the tender words as life ebbed, the final despair: and the whole with the authority of supreme victory. I need not elaborate. Can there be any doubt that the power of Christianity lies in its revelation in human life what Plato taught in theory. [36]

The Victory of Persuasion over Force

Plato had taught that the divine agency was persuasive, relying on reason, not coercion, to accomplish the world’s creation. Plato also taught that it was a part of the reordering of the human person by virtue to recover the primordial reliance on reason and persuasion by which the world was created and by which human beings recover an original reasonableness and harmony. This view has obvious implications for political philosophy and political practice. Human freedom and flourishing are dependent upon the emergence of ever-greater harmony and reasonableness in human society, including its political organization.

For Whitehead, “The progress of humanity is defined as the process of transforming society to make the original Greco-Roman/Judeo-Christian ideals increasingly practicable for the individual members.” [37] The project of human civilization and every human society and political institution is, therefore, advanced by achieving the victory of persuasion over force. [38] Recalling the words of Plato, Whitehead writes:

The creation of the world—said Plato—is the story of persuasion over force. The worth of men consists in their liability to persuasion. They can persuade and can be persuaded by the disclosure of alternatives, the better and the worse. Civilization is the maintenance of social order by its inherent persuasiveness as embodying the nobler alternative. The recourse to force, however, unavoidable, is a disclosure of the failure of civilization, either in general society or in a remnant of individuals. [39]

Against Hobbes, Whitehead holds that persuasion has always been a part of human society and denies that force is the defining characteristic of human society. He disagrees that human society is “a war of everyone against everyone else.” The social and persuasive side of society may even be older than the recourse to force. The love between the sexes, the love of parents for children and families for one another, and even the communal love of small groups are probably older than brute force as a fundamental aspect of human society. In other words, Whitehead sees that a philosophy compatible with the best understanding of reality must, in every area, abandon the Newtonian emphasis on material objects and force.

This does not mean, however, that force is not an inevitable characteristic of society, for there is and always will be a need for laws, structures, and their enforcement and defense. Forms of social compulsion are an outgrowth of the need for social coordination but are (or at least should be) of themselves the outgrowth of reason. [40] Interestingly, Whitehead believes that Commerce is an essential component in the movement from force to persuasion, for commerce depends upon private parties reaching agreements without recourse to force, which tends to build the capacities for reason and persuasion that a free society requires. [41] The importance of persuasion is consistent with the emphasis on the role of love, cherishing, conversation, and dialogue in human society.

Freedom and Order

Whitehead believes that freedom of thought, speech and action are fundamental to social progress. However, there is always a social need to balance what he calls Individual Absoluteness and Individual Relativity. [42] Generally, Individual Absoluteness refers to the area of human freedom in a society, and Individual Relativity refers to the inevitable need for individuals to limit their freedom for the good of society as a whole and other human beings. In this dichotomy, there is a recognition of how social organization and harmony require some limitations on human freedom.

Creating a harmonic balance between the desires and wills of individuals and the maintenance of a sense of social solidarity in a free society requires an understanding of the relational environment from which the individual emerges and its needs for stability in the midst of unfolding change and how individual freedom results in the emergence of a gradually evolving society. There is always an element of chance in how societies evolve, and the resolution in any given community of the tension between freedom and order can seem the arbitrary result of chance—as it sometimes is. [43]The rate and seriousness of social change can vary within a society over time. If existing institutions are working well, and the citizens and centers of power are relatively content, the rate and dimension of change may be slow. In other situations, the rate of change may be significant. [44]

The adjustments required within a society are determined mainly by what Whitehead calls Instinct, Intelligence, and Wisdom. Instinct, which relates to what Peirce calls “habit,” are inherited modes of organization and action that have become customary for society due to inheritance, individual, and environmental factors. Intelligence includes those theoretical factors that are uncovered by human rational inquiry. Wisdom refers to how instinctual and theoretical elements intertwine in the practical accomplishment of social progress. Wisdom can be of greater or lesser effectiveness depending upon the ability to coordinate and incorporate the primary facts of human existence in decision-making. [45]

In the end, social progress is made when human actors in the social arena make wise decisions impacting the evolution of human societies, including their political organization. In the same way, social regress occurs when human actors make unwise decisions concerning the evolution of human society, including its political organization. Finally, there is no avoiding this result because every human decision, great and small, impacts the universe in some way, creating a future, opening up some possibilities, and closing others.

In the midst of all this is each human actor making decisions. These decisions impact the human society in which the actor is located for better or for worse. The activity of free human actors is the foundation of all human thought, and any form of tyranny is antithetical to the emergence of a harmonious social order. In a particularly important passage, Whitehead notes:

A barbarian speaks in terms of power. He dreams of the superman with the mailed fist. He may plaster his lust with sentimental morality… But ultimately, his final good is conceived, as one will imposing itself upon other wills. This is intellectual barbarism. [46]

It takes a little imagination to see that Whitehead is referring to Nietzsche. Writing in the United States on the verge of the Second World War, with the terrible political results of Nietzschean thought evident in Germany. Whitehead understood, as we sometimes forget, that freedom requires a willingness to love, reason, persuade, and forgo all forms of force unless absolutely required by the circumstances. The example of Nazi Germany and the various disasters of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century is a clear argument for adopting a “politics of reason and relationship,” called agapio-sophism.

Conclusion

In the end, Whitehead believes that there are four factors which govern the fate of social groups, including our society:

- The existence of some transcendent aim or goal greater than the mere search for pleasure;

- Limitations on freedom that flow from nature itself and the basic needs of human beings;

- The tendency of the human race to resort to compulsion instead of reason, which is fatal to social growth and flourishing if extended beyond necessary limits and

- The importance of persuasion that relies upon reason and agreement to resolve social problems. In the end, it is the way of persuasion that holds the hope for social and human flourishing. [47]

Whitehead is important for a sophio-agapic analysis of justice. Through his concept of eternal objects, Whitehead is a noetic realist. He believes that values have a form of reality that can impact events and the evolution of any society, especially a complex political society. As a logician, physicist, and philosopher, his work in developing his metaphysical system indicates an orderliness to reality that can be examined by science and other disciplines, including political philosophy. Finally, his notion of “divine persuasion” is similar to Peirce’s notion of an agapic aspect of reality, including social reality. For Whitehead, human reason and emotions are essential in society, including its political organization. Whitehead’s organic, relational view of reality extends to his view of society and encourages attention to the relationships that make up society beyond mere law and power.

In setting out his organic and social vision of reality, Whitehead is highly sympathetic to a harmonic vision of society and the goal of social justice. What is sometimes referred to as a harmonic theory of justice is also an aesthetic theory of justice. [48] In the end, whitehead is captured by a vision of the search for beauty that dominates all efforts to create a better society in every area. Thus, he says:

Science and Art are the consciously determined pursuit of Truth and of Beauty. In them, the finite consciousness of mankind is appropriating as its own infinite fecundity of nature. In this movement of the human spirit types of institutions and types of professions are evolved. Churches and Rituals, Monasteries with their dedicated lives, Universities with their search for knowledge, Medicine, Law, methods of Trade, – they all represent that aim at civilization, whereby the conscious experience of mankind preserves for each use the sources of Harmony. [49]

In the end, Whitehead’s vision is a sophio-agapic vision. A vision of a world in which the human search for truth and beauty is a search for harmony. Human society, complete with harmony and disharmony, is a never-ending, evolutionary project in which each person and society can participate in unfolding a better and more just society.

Copyright 2023, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York, NY: Free Press, 1925, 1967), from now on “SMM.”

[2] Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York, NY: Free Press, 1929, 1957), at 90. Hereinafter, “PR.”

[3] A. N. Whitehead, Adventure of Ideas (New York, NY: Free Press, 1933), hereinafter “AI”.

[4] A. N. Whitehead, Modes of Thought (New York, NY: Free Press, 1938, 1968).

[5] SMM, at 132.

[6] Whitehead uses the terms “actual occasions” and “actual entities” almost interchangeably. For this reason, I think it might be best to consider a more general term.

[7] PR, 90.

[8] Steven Shaviro, “Deleuze’s Encounter With Whitehead” http://www.shaviro.com/Othertexts/DeleuzeWhitehead.pdf (Downloaded July 18, 2022).

[9] PR, 96-98.

[10] SMM, 132-133.

[11] Id, 40.

[12] Id, 118.

[13] This is not the place for a discussion of these phenomena. For those who would like a deeper discussion, see John Polkinghorne, ed, “The Trinity and an Entangled World: Relationality in Physical Science and Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2010). I have examined this phenomenon before in a blog entitled, “Politics and the Order of the World” at www.gchristopherscruggs.com (July 8, 2020).

[14] SM, 152.

[15] AI, 230.

[16] Id, 46.

[17] Id, 41.

[18] It should be obvious that the words, “know,” sense” or “feel” are used metaphorically. Subatomic particles do not have central nervous systems or brains and are not capable of knowing, sensing, or feeling in human terms. Nevertheless, there exists something at the subatomic level that is best described by reference to the human experience.

[19] AI, 230-233.

[20] SMM, 69.

[21] John Polkinghorne, The Way the World Is: The Christian Perspective of a Scientist (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1983), 22.

[22] PR,128.

[23] Whitehead makes a substantial contribution towards the development of “dual aspect monism” characteristic to more recent thought.

[24] It is beyond the scope of this paper, but the fundamental relatedness and meaningfulness of all reality has ecological as well as political implications.

[25] PR 27, 90.

[26] SMM, 132-133.

[27] PR, 26

[28] Id, 105

[29] Susan Shottliff Mattingly, “Whitehead’s Theory of Eternal Objects” A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy. I am indebted to her for portions of this analysis.

[30] It is beyond the scope of this analysis to exhaustively look at Whitehead’s notion of God. He did view God as an essential element of his metaphysical system as the ground of the order and creative potential of the universe.

[31] Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York, NY: The McMillian Company, 1936), 88.

[32] In Whitehead’s system all actual occasions have both a physical and a mental pole. Thus, intelligibility and the potential for the emergence of mind goes all the way down into the smallest actual entities in the universe.

[33] AI, 166.

[34] Id, 160.

[35] Id, 161. It is beyond the scope of this blog, but Whitehead believes that it is not the existence of dogmatics and religious theories that are the problem with religion, but the attitude of finality with which these opinions are voiced. In this, Whitehead echo’s Pearce. The theories of theologians are evidence of the importance of reason to Christian faith, and reasonableness is one of the ways in which brute force is overcome.

[36] Id, at 167. Plato had taught that the divine agency was persuasive relying on reason not coercion to accomplish his goal.

[37] Id, 17.

[38] Id, 25.

[39] Id, 83.

[40] Id, 69.

[41] Id, 70-84. This is a most interesting discussion in which Whitehead deals with Malthusian economics, and its limitations.

[42] Id, 43.

[43] Id, 44.

[44] Id, 45.

[45] Id, 45-7

[46] Id, 51.

[47] Id, 85-86.

[48] Id, 261. In his chapter on beauty in AI, Whitehead speaks of harmony as the objective of the search for beauty. He also describes the way in which disharmony d

(destruction) and harmony are related. Disharmony requires the searcher for harmony to seek a higher and greater harmony, a new harmony. In the same way, each perception of harmony leads to a perception of its inadequacy, which leads to a greater harmony. This is the aesthetic ground of the progress of justice in society.

[49] Id, 272