One of the most remarkable (yet commonsensical) revelations from the research for this blog was the understanding that it is not enough for leaders to simply acknowledge their shadow; they must also learn to manage it for the benefit of the institutions they serve. For better or worse, the unconscious motivators that leaders hide from themselves impact the lives of the organizations they lead. There is truth to the saying that we humans cast a shadow, and leaders cast a particularly large one. [1]

One of the most remarkable (yet commonsensical) revelations from the research for this blog was the understanding that it is not enough for leaders to simply acknowledge their shadow; they must also learn to manage it for the benefit of the institutions they serve. For better or worse, the unconscious motivators that leaders hide from themselves impact the lives of the organizations they lead. There is truth to the saying that we humans cast a shadow, and leaders cast a particularly large one. [1]

The Shadow

As previously mentioned, the “shadow” consists of an accumulation of unacknowledged and, therefore, untamed emotions, motives, and thoughts, both good and bad, that influence our behavior. The term “shadow” signifies that consciously hidden and submerged aspects of our personality operate in the background, within our unconscious, where they can direct and influence our actions without our awareness or control.

This shadow’s unconscious feature makes it significant and potentially dangerous. Let me provide an example. Mr. X grew up in a dysfunctional family. His father was repeatedly unfaithful to his mother, who coped by drinking excessively. Although his father was a moderately successful businessperson, he fluctuated between extreme prosperity and near bankruptcy.

Additionally, the businesses he managed experienced high turnover rates. Eventually, he was compelled to retire from the company he founded. X is also an entrepreneur. He similarly cycles between extreme prosperity and bankruptcy. Like his father, he is unfaithful to his wife and trusts no one. Similar to the organization his father built, the company he created is characterized by internal conflict, a lack of trust, and poor teamwork.

X recently visited a psychologist for help. The psychologist promptly identified the behavioral similarities between X and his father. He also noted, in a constructive manner, that X’s lack of trust had become systemic within his company. He recommended a counseling period along with specific actions to rebuild healthy trust and teamwork in the workplace. X’s shadow was infecting not only his performance but also the performance of others in the company.

Now, let’s look ahead five years. X has successfully confronted his shadow. He has become more trusting and is focused on fostering a positive atmosphere in his company. Interestingly, he recently embraced Christianity and has been working diligently to restore his marriage, which was severely impacted by his unfaithfulness. A trade publication recently featured a positive article about his company, highlighting its low employee turnover for a business in his industry.

This story illustrates the difference between a negative and a positive shadow. Unconsciously, X had harmed his company through his behavior. Once he became aware of his shadow and changed his actions, he began positively impacting his employees, consciously and unconsciously. Not only did he become more trusting and cooperative, but everyone else in the company followed suit. X transitioned from casting a negative shadow to casting a positive one.

We Know More Than We Can Say

The philosopher Michael Polanyi coined a significant phrase in this context: “We know more than we can say.” [2]In every area of human inquiry and activity, we often act based on information, beliefs, worldviews, and prejudices that unconsciously guide our behavior. It can be as simple as holding a hammer. When I hold a hammer while nailing, I am often unaware of how my hand grips it; my focus is on the hammer’s head and the nail. I’m aiming to hit. However, tacit knowledge is even more crucial in more complex areas. In all aspects of life, humans interpret the world through feelings, ideas, and concepts we have internalized to understand and operate in the world as we perceive it. [3] Unfortunately, we do not always interpret the world accurately; unconscious motives and emotions often guide us.

When I lead a business and engage with people daily, I unconsciously apply my feelings about others to my relationships- including their trustworthiness, abilities, loyalty, and a variety of other factors. Most of the time, this occurs without conscious thought. For example, if someone comes into my office and suggests a course of action, I will immediately respond, “ Sure, go ahead,” if I trust that person and view them as confident. Conversely, if I doubt the person, I say, “Let me think about it. ” In addition, in many situations, I have to consciously remind myself that this person may be right even if I don’t necessarily like or admire this person. On the other hand, I have to constantly remind myself that this person might be wrong even if it’s a person I like and admire.

You can see why leaders need to be in touch with their unconscious drivers more than other people. Simple things, like being self-aware when you’re moving too fast and overworking, are essential for a leader, especially if you’re given (as I am) to overperformance. Otherwise, mistakes can be made.

We Emerge from a Family System

Human beings from the beginning of time to the present have emerged from a family system. It doesn’t matter what society or culture you’re in; you are born from the union of a man and woman, and for a period during infancy, you are completely helpless and dependent on others. During this time and into our young adulthood, we are unconsciously shaped by the culture and family system into which we were born. Unconscious programming can follow us into adulthood for better or for worse.

Since there are no perfect families, everyone should come to terms with the family system from which they emerged. I like to tell a funny story about my wife and I. I come from a family that loved to argue about politics and religion at meals. We didn’t think we had had a good dinner unless we argued about something. My wife came from a family system in which politics and religion were not discussed in social situations. We have somewhat different instincts when speaking out about politics and religion. I’ve learned something from her, and she has learned something from me. We have become more conscious of our family systems and how they molded our personalities.

Two very helpful tools are becoming aware and conscious of our emotions and family history and understanding the unconscious drivers of our personality.

Becoming Aware of Our Emotions. It is very difficult for most of us, especially males in our society, to connect with our unconscious emotional state. One of the most helpful things we can do is spend some time each day reflecting on the positive and negative emotions we experience throughout the day. In the last blog, we discussed the Ignatian discipline of recognizing consolations and desolations. In simpler terms, we need to be mindful of the positive and negative emotions we experience daily. Engaging in this practice regularly, over an extended period, is essential to be sure you properly understand the feelings that subconsciously guide you.

The previous illustration demonstrates the process. When X became involved in counseling, he began to write down his emotions. Over time, he discovered that distrust and fear of others, along with concerns about what they might do or think, significantly influenced his emotional life. This affected both his family and business. He recognized that his father also tended to distrust others. This trait had been instilled in him at such an early age that he understood its impact on his behavior.

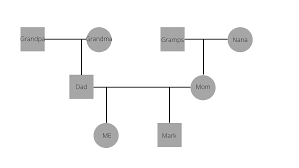

Genograms. Another helpful tool is creating a diagram of your family history, known as a “genogram.” A genogram is a visual representation of your family’s relationships, structure, and composition, including key relationships, character traits, significant life trauma, medical information, and other details. It serves as a tool to help you understand the family system from which you emerged.

Genograms. Another helpful tool is creating a diagram of your family history, known as a “genogram.” A genogram is a visual representation of your family’s relationships, structure, and composition, including key relationships, character traits, significant life trauma, medical information, and other details. It serves as a tool to help you understand the family system from which you emerged.

In creating a genogram of your family, it is essential to ensure that you have your parents, siblings, and children included in the chart. If you can push back to grandparents and great-grandparents, it’s also helpful. In my case, I know a good bit about my parents and grandparents but not as much about my great-grandparents and almost nothing about my great-great-grandparents. I do, however, know one piece of information about a great-great-grandparent that’s important for our family history: he died pretty young, and as a result, the family moved from being middle class to being poor. I think this trauma has impacted future generations up to mine.

The recommended information for inclusion in a genogram includes marriages, divorces, children, and significant traumatic events (such as an early death), as well as issues like alcoholism, drug dependency, domestic violence, sexual misconduct, and other factors that may impact future generations. I have provided a chart to help you get started. Additionally, various online resources can assist you in using symbols to represent specific types of dysfunction. One of the most important considerations is whether the family system functioned effectively. For instance, if one or more children left home at an early age and had no further contact with their parents or grandparents,

It indicates a problem. Returning to my illustration of X, let’s suppose that while creating a genogram, he discovers that not only was his father repeatedly unfaithful to his mother, but his grandfather and great-grandfather were also unfaithful and even fathered illegitimate children. This would indicate a deep wound in the family system that X needs to address. Having completed more than one genogram over the past several years, I have found that each case contributed to my self-understanding.

At this point, offering a personal disclaimer or at least some words of wisdom is necessary. The purpose is not to blame our problems on our parents and ancestors but to help us understand ourselves and change. One of my great-grandparents came from Scotland at a very young age. His parents died almost immediately, leaving him to care for himself and his siblings. He worked in a physically demanding job throughout his life. He could be a heavy drinker, had a temper, and could be occasionally violent, including to a hyperactive and not very well-behaved little boy. I can only say that if I had experienced the same life as he did, I might have become just as violent and just as heavy a drinker. I don’t blame my great-grandfather for his behavior or my weaknesses and temper. I understand, love, and hope that he found healing in heaven. This is the attitude we should adopt when creating a genogram. We’re not here to blame; we’re here to learn and seek healing.

Conclusion

The shadow and its impact on our lives and the lives of those around us is an important concept. It’s important in families, churches, small groups, businesses, schools, and every social institution we are part of. I’ve emphasized the importance of leadership and the shadow of a leader. That should not blind any of us to the fact that our behavior impacts the entirety of our relationships. In other words, my shadow may not have as significant an impact as the shadow of the president of the United States. Still, it impacts me and all my social relationships, including my citizenship, our country’s character, and even our world’s character. Therefore, it’s worth taking the time to do a little “shadow management.”

Copyright 2025, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] As mentioned previously, Peter Scazzero, The Emotionally Healthy Leader: How Transforming Your Inner Life Will Deeply Transform Your Church, Team, and World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017). See also, Emotionally Healthy Discipleship: Moving from Shallow Christianity to Deep Transformation (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021). Emotionally Healthy Spirituality, Updated Ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017). The Emotionally Healthy website is https://www.emotionallyhealthy.org/. The materials needed to guide individuals through emotionally healthy discipleship training are available on the website and most Christian and secular online book retailers. The Emotionally Healthy Spirituality and Relationship Courses are offered as the “Emotionally Healthy Disciples Course,” which includes books, study guides, teaching videos, devotional guides, and teaching aids.

[2] Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966), 4. The actual quote is, “We know more than we can tell.”

[3] Id, at 29.