Candid portrait of American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer John Dewey standing in a wooded area, 1935. (Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images).

Candid portrait of American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer John Dewey standing in a wooded area, 1935. (Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images).This week, I had a series of blogs on my mind, ranging from my practical analysis of our policies in the Middle East to a meditation on discipleship to continuing to dialogue with John Dewey regarding political philosophy. In the end, I decided that I was going to devote this week’s blog to John Dewey and the subject of logic and public policy formation. As with my last blog, I’m somewhat dependent upon the work done by Donald Gelpi in his masterful work, The Gracing of Human Experience and a friend for suggesting that I read him. [1]

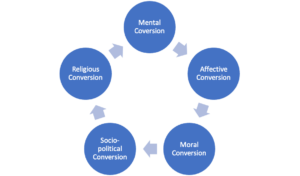

Last week, I devoted myself to his notion of conversion that goes far beyond spiritual conversion to the conversion of the mind, the heart, the morals, and the politics of Christians. His philosophical analysis of conversion can be applied to secular and religious conversions. He proceeds with his analysis by looking at some of my favorite philosophers, including C. S. Peirce, Josiah Royce, Herbert Mead, and John Dewey.

Readers of the blog will remember that I am attached to the notion that our political culture suffers from a lack of authentic dialogue. It is to say that so much of our politics assumes that the political process is all about debate, argument, voting, and winning or losing. As one of my professors in college put it, “Politics is about power.” At the time, I agreed. However, as the years have gone by, I find myself disagreeing at a fundamental level. Politics is about power. However, democratic politics cannot be conducted without community, dialogue, and the search for mutual understanding. At its deepest level, politics is about community.

The subject of logic plays a vital role in dialogue. In a democracy, often people think of dialogue as various people and groups just saying what they believe. They don’t have to have a reason for what they think; what they’re considering doesn’t have to be logical; it’s enough that they have an opinion. At some level, this is a harmless illusion. However, for progress to be made, dialogue has to proceed on the assumption that we are searching for practical solutions to social problems, which will be revealed to us as a result of a process of inquiry.

Three Modes of Logical Inquiry

Most people are familiar with two methods of logical inquiry: “induction” and “deduction.” Peirce introduced a third, intermediate logic called “Abduction.” All human thinking, if it is to be valid, must consist of manipulating signs in one or more of these three logical ways. [2] Briefly, the three methods can be defined as follows:

- Induction. Inductive reasoning begins with specific observations and proceeds to a generalized conclusion that is likely but not certain in light of accumulated evidence.

- Deduction. Deductive reasoning begins with general rule and proceeds to a guaranteed specific conclusion in a limited case. If the original assertion is true, the conclusion must be valid in deductive reasoning.

- Abduction. Abductive reasoning begins with limited and necessarily incomplete observations and proceeds to the likeliest possible explanation for what experiencehas revealed.

Abductive logic yields the kind of daily decision-making that does its best with the information that can be acquired, which often is incomplete and draws a conclusion based on the best available evidence. It then tests its findings.

Abduction and Reasonable Inquiry

Importantly, abductive reasoning is at the center of a scientific approach to understanding and at the center of other forms of intellectual progress as well. Neither induction nor deduction can provide intellectual explanations of phenomena. All scientific inquiry begins with a problem and one or more hypotheses or ideas about the best answer or solution to the problem. This has important implications because it “dethrones” the positivist notion of knowledge as based upon “the facts alone.” Instead, all facts are identified and interpreted within some interpretive framework. Science, for example, is interested in developing and analyzing facts. Still, those facts are developed and analyzed within a theoretical matrix of reasonableness based on the scientific method.

Science is not the only area of life in which one has to reason from a hypothesis to a conclusion that can be tested against the facts. This is, for example, what detectives do when solving a crime. (“I think the Butler did it; now I have to find evidence that supports that conclusion.”) It is essential in business. (“I think this new product will sell; however, before investing a lot of money, I need to do market research to be sure I’m correct.” It is true in law. (“I think the right way to structure this transaction is as follows. But I need to test out whether or not my theory is correct.”) It’s true in Government. (“I think the best policy in this situation would be to raise taxes, but I still have to think and discover what facts are in support of my opinion.”)

Fallibilism and Humility

In addition to testing, I have to remain open to the possibility that my hypothesis is false and thus accept the existence of contrary facts. This involves two crucial principles that underlie abductive inquiry:

- Fallibilism. All wise thinking includes the possibility that I might be wrong. Fallibilism holds that no empirical belief (theory, view, thesis, etc. ) can be conclusively proven in a way that eliminates the possibility of error or limitations. There always remains doubt as to the truth of any empirical matter.

- Humility. Understanding that human understanding is limited, partial, and often wrong, I humbly open my mind to evidence contrary to my ideas.

Unfortunately, American public debate sadly lacks both a sense of the limits of human knowledge and humility about human availability and openness to contra views. This is why, even in families, it is difficult to have rational discussions about specific political figures at this time.

Abduction and Dialogue

Deep within the logical views of both Peirce and Royce is the notion that all thinking is tripartite. First, outside of myself, there is a reality being investigated (the object). Second, there exist my ideas (or my group’s ideas) about that object. Finally, there is the interpretation of my ideas (or my group’s ideas) of that reality by a third party, who is the interpreter.

In many ways, this is the most complicated area of all in public discourse. In a nation of 300 million people, it shouldn’t be surprising that there are thousands of interpretations of the same reality. There are many different interpretations of any one group’s ideas about any political reality. Public officials, if they are to act logically and wisely, have to somehow analyze, usually in groups, that reality and all the various ways in which it is interpreted and, from that, develop a course of action (the policy choice).

The Logic of Dewey

This gets me to the role of logic in the thought of John Dewey. John Dewey considers his view of logic as “instrumentalism.” [3] That is to say, logic exists as an instrument by which human beings make decisions. Because Dewey was a materialist, he considered that our notions of logic have two sources:

- First, the universe’s evolution created species that survive a way of looking at reality that was pragmatically useful for survival. That pragmatic way of looking at reality in the quest for survival is a natural source of logic.

- Second, all human beings exist in a human society that has evolved over time. Certain ways of thinking and looking at reality were conducive to that society’s success and its challenges. Thus, culture is also a source of logic. [4]

In other words, deduction, induction, and abduction did not emerge from some ideal realm, as Plato might have thought. Still, instead, these forms of reasoning evolved as a part of human beings facing reality and trying to adapt successfully to that reality and the challenges it presents. If we go this far with Dewey, we can see a natural connection between logic and political theory. Demanding that our public debate be rational and logical is just part of demanding that it successfully lead to policies that serve the common good.

On a purely instrumental level, we can see the importance of Dewey’s insight. However, I don’t think either Pierce or Royce would have entirely agreed with Dewey’s conclusions, nor do I think that they are consistent with the deepest understandings of modern science. For them, the universe itself displays a kind of rationality, from its inception, rationality, that we see logically developed in the mathematics of, for example, quantum physics. This rationality that is embedded in the universe is in some way prior to any human evolutionary rationality, and any human culture.

From a Christian perspective, the universe demonstrates an underlying rationality because it was created by a logical and rational creator, who, in love, created the universe that we are privileged to discover on a number of levels: scientific, religious, cultural, economic, political, and otherwise. This does not mean that aspects of this rationality that we observe in the universe is not a matter of evolutionary success. On the assumption that evolution and the gradual development of human culture were built into the potential of the universe from its very first days, then one believes it over millions of years, the rationality that we observe in the universe and in human culture gradually ever so gradually emerged over time.

The great British physicist turned religious scholar, John Polkinghorne, put it this way:

Certainly, our powers of thought must be in such conformity with the everyday structure of the world that we are able to survive by making sense of our environment. But that does not begin to explain why highly abstract concepts of pure mathematics should fit perfectly with the patterns of the subatomic world of quantum theory or the cosmic world of relativity, both of which are regimes whose understanding is of no practical consequence whatsoever from humankind’s ability to have held its own in the evolutionary struggle. Nor does the fact that we are made of the same stuff (quarks, gluons and electrons) as the universe serve to explain how microscopic man is able to understand the microcosm of the world. Some fairly desperate attempts have been made along these lines nevertheless showing how pressing is the need to find an explanation for the significant fact of intelligibility. [5]

This observation sits at the ground of my view that Christians ought to be able to engage in public life and public discourse and state their views on Christian grounds, so long as those views are stated logically and with reference to the reality of other positions. We cannot necessarily expect that strictly Christian views will be accepted in every matter of public debate, and in fact, we should be consciously aware of the fact that our views might be wrong, but nevertheless, Christians should be entitled to state their views on public matters.

Instrumentalism and Public Policy

It should be obvious that the notion that reason has an instrumental function and that logic is in itself instrumental has important consequences for the development of public policy and the conduct of public debate. Public policy is about adopting strategies and tactics that will lead society to a better state. As such, it is an essentially logical process. Dewey, while not directly talking about politics and political theory, put it this way:

It is reasonable to search for and select the means that will, with the maximum probability, yield the consequences which are intended. It is highly unreasonable to employ as means, materials, and processes that would be found, if they were examined, to be such that they produce consequences that are different from the intended end, so different that they preclude its attainment. [6]

Applied to the realm of public discourse, this principle can be stated as follows: Public policy is unreasonable if it adopts policies and processes that, under examination, are likely to produce consequences contrary to the public good and the intended result. In public life, politicians should be willing to subject their views to criticism and modify their policies where the best evidence indicates that the public good intended cannot be acquired by the means chosen.

Wise public policymaking involves using all the forms of logic suggested above. We must guess what the wisest public policy is (our hypothesis). We must gather facts that either support or do not support our hypothetical public policy. Finally, in reaching our conclusions, we must be sure that they’re not deductively incoherent. This is a part and parcel of proving or disproving the hypothesis.

Conclusion

I will spend a couple of more blogs on the fascinating question of the role of logic in public policy. It’s a subject that I think deserves our attention. We live in a society where the media and other specific instruments often promote a kind of decision-making based on what “I want” (or what my group wants). This kind of decision-making does not lead to sound public policy. It needs to be replaced. Furthermore, all ideologically driven policy formulations will likely be unsuccessful because they arrive at a reasoning process based on what I think an ideal society should look like. Both Marxist and hyper-capitalist policy thought are subject to weakness.

Copyright 2024, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Donald L. Gelpi, The Gracing of Human Experience: Rethinking the Relationship between Nature and Grace (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2001).

[2]. This section of the blog relies on my analysis of Peirce in G. Christopher Scruggs, A “Sophio-Agapic” Approach to Political Philosophy: Essays on a Constructive Post-Ideological Politics (Unpublished Manuscript, 2024).

[3] John Dewey used this term to describe his version of pragmatism. In this sense, logic is an instrument for evaluating ideas and policy alternatives. This is to be distinguished from instrumentalism, which refers solely to the means and use of power.

[4] John Dewey, Logic: The Theory of Inquiry (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 1938), 23-60.

[5] John C. Polkinghorne, Science and Creation: The Search for Understanding (Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press, 2006), 30.

[6] Logic, at 10.