This week, I examine what is sometimes called the “Dark Night of the Soul,” an experience that Peter Scazzero refers to as “the Wall.” [1] One of the exciting features of Scazzero’s work is that it exemplifies what I sometimes call the “Post Modern Recovery of the Ancients.” In the case of the Wall, he is recovering the ancient church’s spirituality that surrounds how God is present in his absence, provides light amid darkness, and works in spiritual pilgrims to purify them from barriers to the fullness of what God has for them. Surprisingly, this ancient notion is relevant to secular and religious leaders today.

This week, I examine what is sometimes called the “Dark Night of the Soul,” an experience that Peter Scazzero refers to as “the Wall.” [1] One of the exciting features of Scazzero’s work is that it exemplifies what I sometimes call the “Post Modern Recovery of the Ancients.” In the case of the Wall, he is recovering the ancient church’s spirituality that surrounds how God is present in his absence, provides light amid darkness, and works in spiritual pilgrims to purify them from barriers to the fullness of what God has for them. Surprisingly, this ancient notion is relevant to secular and religious leaders today.

It is a fundamental notion of Christianity that humans fall short in life (are sinners) and suffer from disordered desires and attachments. St. Augustine famously declared that we love what we shouldn’t love and love the right things incorrectly. We seek our comfort, our pleasure, and our own will. We value what we want more than we value what God wants. We commit wrongdoings, even if only in our hearts.

Secular thinkers generally conceive the human condition as burdened by psychological trauma inherited from childhood and inadequate education and nurturing. The result, however, is just the same—we are less than fully functional, healthy, and moral human beings. We miss the mark of the goals we and others have for our lives. Leadership places extraordinary pressures and burdens on those who exercise it. [2] Whatever “cracks” exist in their personalities are likely to be exacerbated by the pressures leaders face.

The past two blogs emphasized the importance of feeling emotions, positive and negative, understanding the unconscious drivers that impact our leadership and the impact it has on others, and fostering what we referred to as a “positive shadow,” which is a subconscious emotional and spiritual reality that encourages the best functioning of the organizations we lead. This week, we will talk about failure and the need to grow internally through periods when the positive aspects of leadership (success) are lacking in the context of the Christian notion of the Dark Night of the Soul.

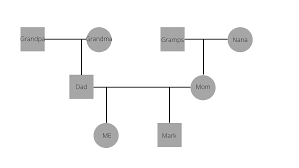

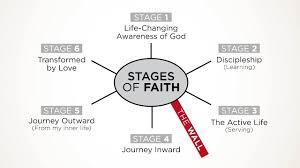

The Wall and Dark Night of the Soul

First, we need to define what we are discussing when we speak of “the Wall” or “Dark Night of the Soul. “Secular readers will have to ponder the concept a bit, but eventually, the idea’s secular importance will dawn on all readers. At the beginning of the religious life, there is usually a honeymoon. You have made a spiritual commitment, received some initial discipleship training, attended worship and other services, started studying the Bible or other religious literature, learned the rudimentary elements of prayer and meditation, and found life different and better.

First, we need to define what we are discussing when we speak of “the Wall” or “Dark Night of the Soul. “Secular readers will have to ponder the concept a bit, but eventually, the idea’s secular importance will dawn on all readers. At the beginning of the religious life, there is usually a honeymoon. You have made a spiritual commitment, received some initial discipleship training, attended worship and other services, started studying the Bible or other religious literature, learned the rudimentary elements of prayer and meditation, and found life different and better.

The problem from a religious perspective is that all of this is, in a way, selfish. We love God or engage in a spiritual community for what we can gain from it. When I reflect on my early religious life, this is exactly what I experienced. I became a Christian in a small group in Houston, Texas, in the late 1970s. I immediately encountered profound spiritual growth. I learned how to study the Bible, began to pray, and volunteered in various public services, including a local mission, church youth activities, and a Sunday School class. I met my wife, fell in love, and started a family. Through all of this, I experienced one long period of consolation and blessing from God, which lasted several years.

In secular callings, there is a similar experience. One decides on a career, for example, law. One studies and achieves the necessary licenses and education. When one first goes to work, one grows rapidly. Everything is new, and every day involves growth as a professional. Sure, there are hard times, which one expects, but overall, a life goal is being accomplished. In the case of lawyers, they may begin to participate in a local or even state bar association.

Unfortunately, this stage does not last forever. For most Christians, there comes a point when they experience spiritual dryness, a feeling that their prayers are hitting a glass ceiling. Prayers go unanswered, and the excitement of religious experience diminishes. Simultaneously, one might face spiritual struggles, including unanswered prayers that seem justified, conflicts within the religious community, and similar challenges. Pastors and spiritual directors consistently caution that these occurrences are neither the dark night of the soul nor the unavoidable ups and downs of life, such as job loss, family issues, moral failures, and so forth. While this is accurate, all of these can be external manifestations or triggers of a Dark Night. The Dark Night or Wall refers to the feeling of God’s absence in the situation.

In the life of most leaders, a similar experience often occurs. For example, let us take the case of a person I will call “Dr. Y.” Dr. Y graduated from a prominent Presbyterian seminary. Dr. Y was a significant success through several more extensive and prominent calls. He was a natural preacher, had good relational and leadership skills, and a practical bent that allowed him to begin ministries and grow churches. Y was a good servant of God, and God was a good servant of Y’s ambitions.

At 45, Y was at the pinnacle of any pastor’s dream career. He was the church’s Senior Pastor, led a sizeable non-profit mission in the city, was a published author, and was much in demand as a speaker and retreat leader. He received a call from a mega-church. At that church, he followed a legendary pastor who took a small rural congregation and turned it into a mega-church in a major city’s suburbs. For the first time, he faced opposition and failure in a call. The congregation constantly compared him to the former pastor. They rejected worship and mission. And managerial changes that Y had successfully instituted in the past. Y was under enormous pressure. Eventually, he suffered a minor self-induced failure. The leadership who called him turned against his leadership. For a time, Y did what any strong leader might do. He worked harder. He studied his Bible, and he prayed. There were no answers to those prayers. Now, Y was lonely, depressed, and questioning his faith. He prayed, but there were no answers.

The events that occurred are of a type that happens to many pastors. They are not the dark night. The Dark Night is the perceived sense of God’s absence during spiritual growth. This is why it is often called “God’s presence in God’s absence.”

Eventually, Y asked for and was given a Sabbatical. For a part of the time, he was with his wife and family. For a part of the time, he went to a Catholic Retreat Center, where he was able to share his feelings of abandonment by God. In the end, Y moved from loving God and ministering to others from a selfish and immature motive to loving God and ministering to the congregation in a selfless way from a center in the unmerited love of God.

Two Aspects of the Dark Night

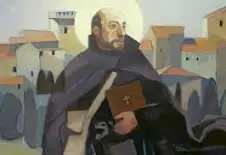

In The Dark Night of the Soul, St. John of the Cross identifies two kinds of Dark Night. The first is a night of the senses. In other words, we don’t feel the presence of God. The second night is a night of the spirit in which God appears absent from our spiritual lives. Saint John of the Cross puts it this way:

In The Dark Night of the Soul, St. John of the Cross identifies two kinds of Dark Night. The first is a night of the senses. In other words, we don’t feel the presence of God. The second night is a night of the spirit in which God appears absent from our spiritual lives. Saint John of the Cross puts it this way:

This Dark Night, a night of contemplation, produces two kinds of darkness or probation in a spiritual person, corresponding to two parts of human nature: the sensual and the spiritual. The first Dark Night is sensual, wherein the soul is purged according to sense, subduing it to the spirit. The second Dark Night is spiritual. During this second night, the soul is purged and stripped, according to the spirit, subdued and made ready for loving union with God. … The first Dark Night is bitter and terrible to sense. The second Dark Night is far beyond the first, for it is horrible and awful to the spirit. [3]

In simple terms, humans need to be purged of our tendency to value things according to our senses and the pleasure they bring us. Beyond the merely sensual, we also value ourselves, that spiritual psycho-somatic unity of mind, body, and soul that makes up our total spiritual personality. This spiritual self must also be purged. Those who can endure this purging of the false self in all its forms find a new spiritual unity and wholeness in which they can love God and others unconditionally and without expectation of personal pleasure.

A Secular Example

“Z” is a successful businessman. After graduating from college, he worked in a major technology company as a salesperson, sales manager, and eventually as part of management. He eventually earned an MBA. At a fairly young age, Z was offered the chance to lead a technology start-up company. He was also successful in that endeavor, and eventually, the company went public.

Recently, Z has hit a wall in his professional career. Things that once brought him great joy no longer provide any satisfaction. In addition, his company has fallen behind in the always competitive high-tech industry. The market niche for his product has changed. Several of his employees have publicly challenged his leadership, and his board of directors has begun to raise questions about it. For many years, he has devoted his life to increasingly larger achievements.

At the insistence of his Board of Directors, he began a relationship with a leadership coach. In a recent session, the coach made a challenging observation. She asked a rhetorical question, “Basically, what you are saying is that up until now, your business career has been about you—your achievements. What about your employees, suppliers, customers, shareholders, and others?” I don’t sense much interest in them.”

After the session, Z reflected on her observation. He recalled reading Jim Collins’s book, Good to Great. [4] One of Collins’s key points is that great leaders display humility, focus their energy on the company instead of themselves, and anticipate and empower potential successors. During a long self-examination and with his coach’s help, Z became aware of this pride and the way success fed his pride. He became aware of his love of money and the luxuries that success brought him. He came to terms with his personal weaknesses and shortcomings. Considering his situation, he recognized the need to set aside his ambition and develop a humble, servant spirit towards his company and all its stakeholders. By doing so, Z broke through a leadership barrier that had held both him and his company back.

Conclusion

Dark Nights, or what might be called “Encounters with a Wall,” are often viewed as negative experiences. In reality, they present valuable growth opportunities. These encounters may be perceived as signs of failure; however, they signify future success. Often, they are resisted as a form of death, yet they serve as a pathway to new and abundant life. This does not imply that they are easy- far from it. But they are essential for anyone, whether secular or religious, to attain the fullness of their potential.

Copyright 2025, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] As mentioned previously, these blogs are based on Peter Scazzero, The Emotionally Healthy Leader: How Transforming Your Inner Life Will Deeply Transform Your Church, Team, and World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017), hereinafter EHL. See also Emotionally Healthy Discipleship: Moving from Shallow Christianity to Deep Transformation (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021). Emotionally Healthy Spirituality,Updated Ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017). The Emotionally Healthy website is https://www.emotionallyhealthy.org/. The materials needed to guide individuals through emotionally healthy discipleship training are available on the website and most Christian and secular online book retailers. The Emotionally Healthy Spirituality and Relationship Courses are offered as the “Emotionally Healthy Disciples Course,” which includes books, study guides, teaching videos, devotional guides, and teaching aids.

[2] EHL, 270.

[3] I have paraphrased this passage from St. John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul, tr. E. Allision Peers (New York, NY: Image Books, 1990), 61. I have simplified the language and tried to make it more readable for contemporary people who are not specialists.

[4] Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap, and Others Don’t (San Francisco, CA, 2001),