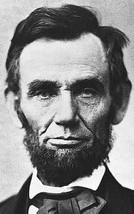

Last week, we looked at the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln to the war’s mid-point in 1863. After the battle of Vicksburg, the Union navy controlled the entire length of the Mississippi reiver, cutting the Confederacy in half. Lee’s army retreated from Gettysburg, morally wounded. The end-phase of the war had begun.

Last week, we looked at the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln to the war’s mid-point in 1863. After the battle of Vicksburg, the Union navy controlled the entire length of the Mississippi reiver, cutting the Confederacy in half. Lee’s army retreated from Gettysburg, morally wounded. The end-phase of the war had begun.

The Union Victory and Lincoln’s Death

Although Lee would prove a capable leader time and time again during the ensuing 18 months, fighting a long retreat, the Army of Northern Virginia never again reached the same level of greatness it achieved during the first half of the war. In addition, in Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln found a general who was willing to both use the industrial might of the North and expend the lives necessary to win a decisive victory. He pounded the Army of Northern Virginia until it was battered into defeat. By April of 1865, Lee’s army was exhausted, surrounded, and unable to continue. On April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Court House, Lee surrendered his army. Although the war would continue for a while longer, by the November 1865, the last holdouts had surrendered.

Lee’s surrender resulted in a national celebration. On April 11, two days after Lee’s surrender, Lincoln spoke to the crowds around the White House, in what would be his last public address. In that speech, he addressed the issues that would have to be addressed in the reconstruction of the nation after the end of hostilities. Three days later, John Wilkes Booth slipped into the President’s box at Ford’s Theatre and shot the president, fatally wounding the 16th President. He died early the next morning.

Without Lincoln’s moral authority and determination to moderate the influence of the Radical Republicans and cajole the Southern leadership into a “malice free” reconstruction, the leadership of the reconstruction took on an retaliatory character, which alienated the South. In addition, Lincoln’s deep dislike of slavery, and the affection the now freed slaves felt towards him because of his leadership in winning their freedom, would not be present to give impulse to the changes necessary to enact into law the victories won on the battlefield as well as to restore the defeated southern states to statehood. His death was a disaster for North and South alike.

13th Amendment

Despite the Union victory, amendments were necessary to embody in the Constitution the freedom declared during the Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation. The Thirteenth Amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, before the end of the war and Lincoln’s death, and was ratified by the states by December 6, 1865. This amendment provided that, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” [1] Its impact was to undo the Dred Scott decision granting property rights in slaves and nationalize the freedom granted to slaves by the Emancipation Proclamation, which was enacted under the president’s war powers, with certain exceptions.

14th Amendment

On April 9, 1868, three years after the War’s end and Lincoln’s death, the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified by the requisite number of states. Section 1 of this Amendment provides as follows:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. [2]

This section of the 14th Amendment has been the most important of the Civil War Amendments, because of its determination that the privileges of United States citizenship, due process of law, and equal protection of the law are not only applicable to the national but also to state governments. Over the years since it was ratified, this amendment has been the subject of much litigation and the vehicle for incorporating many federal rights into the states.

The 14th Amendment contains other provisions that are of importance. Section 2 repealed the “three fifth clause” of the original constitution that failed to fully count the citizenship of black voters was specifically undone. Together with the 13th Amendment, this article clarifies that all males over twenty-one years of age are entitled to vote. This provision also allowed the vote to be denied to those who served in the Confederate government after taking an oath of office to the United States.

Section 3 allows Congress to prevent those who took an oath of allegiance to the U.S. Constitution before the Civil War, from holding office if they “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against the Constitution. The intent was to prevent the President Johnson from allowing former leaders of the Confederacy to regain power within the U.S. government after securing a presidential pardon.

Section 4 prohibited the former southern states from payment of any of the debts they had incurred during the Civil War or from compensating former slave owners for the loss of their property. This prevented Southern states from repaying debts to fund the war, making any future insurrection less possible and preventing those who financed the war from recouping their losses.

Section 5 allows Congress to enforce the provisions of the amendment by appropriate legislation, powers that became of importance in the 20th Century with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Importance of the 14th Amendment

As indicated, the most important of the Civil War Amendments is the 14th Amendment. In recent years, the Supreme Court has applied the protections of the 14th Amendment on the state and local level. [3] For example in Brown v Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the Supreme Court overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson 163 U.S. 537 (1896), ruling that segregated public schools violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. In Loving v. Virginia (388 U.S. 1 (1967), the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia Statute outlawing interracial marriage on the basis that a statutory scheme preventing marriages between persons solely on the basis of race violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In these and other similar cases the court has ruled on cases related to the consequences of the Civil War. [4]

Procedural and Substantive Due Process

It has long been a question of jurisprudence whether due process only protects one’s rights to a fair judicial procedure or whether it has substantive force, protecting personal liberty. The distinction between procedural and substantive due process is an important one. The debate over this issue extends all the way back into English Constitutional history, and the founding fathers and others were not of one mind about whether the Constitution’s due process clauses protected substantive rights. [5] Nevertheless, the Fourteenth amendment has been interpreted throughout its history in substantive ways, not always with positive results.

Before enactment of the 14th Amendment, the decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford 60 U.S. 393 the due process clause of the 5th Amendment was interpreted to protect the rights of slave-owners in the property, a decision that is universally condemned by historians of the court In Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905) the court invalidated a state law creating maximum work hours per week as denying the right of contract, thus reintroducing the doctrine into American jurisprudence. Lochner is not a well-regarded decision of the court and was overturned in West Coast Hotel v. Parish 300 U.S. 397 (1937).

Since West Coast Hotel v. Parish, the Supreme Court has essentially employed a two-tiered analysis of substantive due process claims.

- Legislation concerning economic affairs, employment relations, and other business matters is subject to minimal judicial scrutiny, meaning that a particular law may be overturned only if it serves no rational government purpose.

- Legislation concerning “fundamental liberties” is subject to strict judicial scrutiny, meaning that a law will be invalidated unless it is narrowly tailored to serve a significant government purpose. [6]

This second category of “fundamental liberties” is divided into two sub-categories, those rights which are fundamental because they are within the Bill of Rights and those which are not within the Bill of Rights, but which are deemed fundamental by the Supreme Court. It is this category that has provoked the most controversy. Beginning with Griswold v. Connecticut 381 U.S. 479 (1965) the Supreme Court began a series of cases, most importantly Roe v. Wade410 U.S. 113 (1973), where the court found a fundamental liberty under circumstances where large numbers of people disagreed and continue to disagree. [7]

15th Amendment

1n 1886 Congress proposed the 15th Amendment, which was ratified by the states on July 9, 1868. The 15thAmendment to the Constitution was added to the Constitution to clarify the voting rights of former slaves. It provides that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In its second section, Congress is given the power to enforce the article by appropriate legislation. [8] The 15th Amendment is the final of the three amendments added to the Constitution after the Civil War.

Subsequent to the Civil War, this Amendment was added to ensure the voting rights of former slaves. Initially, the Amendment was successful, but as radical reconstruction gradually failed and the southern states began to pass their own laws concerning voting rights, a variety of measures were enacted that dramatically restricted the voting rights of black citizens, including voting rights laws that created legal hurdles, such as literacy tests, poll taxes, odd districting, and other methods. This is a sad chapter of American and especially Southern American history. De Tocqueville foresaw that the end of slavery would bring about an increase in prejudice and hostility towards the former slaves, and he was correct in his fears.

In Giles v. Harris 189 U.S. 475 (1903) the court refused to hold these laws unconstitutional, delaying full incorporation of the black community into American political society for more than another half-century. [9] However, beginning with Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944), the court began the process of invalidating state laws that interfered with voting rights of minorities. [10] The process was only completed with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Congress was empowered to adopt under the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Conclusion

The Civil War ended the national debate concerning slavery. What politicians had been unable to solve peacefully in the halls of Congress, the Courts, and the Whitehouse, the guns of war resolved on the battlefield. Subsequent to the war, the amendments that have been the subject of this blog were enacted to end both slavery and the legal impediments to former slaves being fully-incorporated into American society. The promise of the enactment took a century to fully accomplish. [11]

The second result of the war was the clear establishment of the national government as supreme, and the end of any theory under which the national government was simply a confederation of state governments. The Civil War Amendments also accomplished this result over time, especially the 14th Amendment.

The second result has not been without its complications for American society. Increasingly the courts have been looked to resolve issues that might have better been resolved by Congress or the state legislatures. Remembering de Tocqueville’s understanding that all the subordinate levels of government were and are vast training grounds for development of the skills and practices of democratic self-government, the loss of both willingness and responsibility of local governments for many issues of life is one to be addressed in the future—and no easy solution comes to mind.

Copyright 2021, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Constitution of the United States of America, Amendment XIII (1865).

[2] Constitution of the United States of America, Amendment XIV (1868).

[3] This process began with Gitlow v. New York (28 U.S. 652 (1925), the Court held that the due process clause of the 14th Amendment protects First Amendment rights of freedom of speech from infringement by the state governments.

[4] Beginning with Griswold v. Connecticut 381 U.S. 479 (1965) the Supreme Court has cited the 14th Amendment in cases involving contraception (Griswold), abortion (Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973)), and the power of states to regulate same sex marriages. (Obergefell v. Hodges 576 U.S. 644 (2015)). This line of cases presents interesting legal issues which may form the basis of a future blog, but lie outside this reflection on the Civil War Amendments.

[5] See, Nathan S. Chapman & Michael W. McConnell, “Due Process as Separation of Powers” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2005406 (2012), (downloaded November 30, 2021).

[6] Substantive Due Process, at https://law.jrank.org/pages/10589/Substantive-Due-Process-Modern-Analysis.html (downloaded November 29, 2021).

[7] This is not the time to discuss this line of cases, which must await our arrival at the 1960’s with its pervasive changes in American society. We will discuss the subject of substantive due process again when we look at the thought of Oliver Wendall Holmes.

[8] United States Constitution, Amendment Fifteen (1868).

[9] One of the tragedies of Giles v. Harris is that it was authored by Justice Holmes, one of the few of his cases to receive almost universal condemnation.

[10] Once again, I cannot go into the series of cases in which the court both denied attempts by blacks and then retreated to support such attempts in this blog. It is, however, a complex and interesting analysis, which I may undertake when we get further along.

[11] For example, the poll tax, which was one of the vehicles used to deprive black persons of voting rights was only outlawed by passage of the 24thAmendment in 1964. In many ways, this is the last of the “Civil War Amendments.”