Some weeks ago, a new friend suggested I read Donald L. Gelpi’s The Gracing of Human Experience: Rethinking the Relationship between Nature and Grace. [1] In this blog, I will not go into the details of his thoughts but instead focus on his analysis of the holistic power of grace to transform human persons. Why is this important for laypersons? It is important because all Christians, to be the kind of disciples we want and intend to be, need to be transformed, not just spiritually, but in our minds, ways of thinking, cultural attitudes, political attitudes, and other ways. The gospel does not transform only a part of me. It transforms all of me.

Some weeks ago, a new friend suggested I read Donald L. Gelpi’s The Gracing of Human Experience: Rethinking the Relationship between Nature and Grace. [1] In this blog, I will not go into the details of his thoughts but instead focus on his analysis of the holistic power of grace to transform human persons. Why is this important for laypersons? It is important because all Christians, to be the kind of disciples we want and intend to be, need to be transformed, not just spiritually, but in our minds, ways of thinking, cultural attitudes, political attitudes, and other ways. The gospel does not transform only a part of me. It transforms all of me.

The Dynamic Process of Conversion

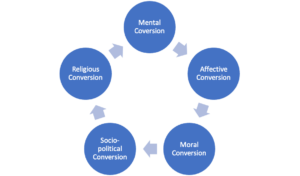

The dynamic process of conversion takes more than one form, each of which reinforces the other. For the purposes of our discussion, let’s look at the following kinds of conversion:

- Religious conversion impacts our view of the nature of the world and ultimate reality.

- Intellectual conversion impacts how we think and visualize the world and ultimate reality.

- Affective conversion impacts our emotional life and our affections

- Moral conversion affects how we view questions of value and ultimate moral claims.

- Socio-political conversion impacts how we see human society and human culture.

These various forms of conversion are not separate but rather exist in a dynamic relationship with one another. As our religious beliefs change, our way of thinking changes. As our thinking changes, our emotions change. As our emotions change, our morals change. As our morals change, the way in which we see humans, society, and culture changes. This interconnectedness is a testament to the comprehensive nature of grace’s transformative power.

I decided this week to insert a little graphic that illustrates the dynamic form of conversion. It would go something like this:

The point of the graphic is to illustrate the absolute interconnectedness of a conversion experience.

In the past, I’ve had an opportunity to talk about the interconnectedness of reality. At the deepest levels of reality, things seem to exist in a state that physicists call “entanglement.” If this is the case, it should not surprise us that human beings exist in a complex, interconnected dialogue between the various universes they inhabit: religious, intellectual, emotional, moral, and social-political. These universes can be separated for purposes of analysis, but they cannot be separated for purposes of everyday life. Therefore, a change or conversion in any of these universes automatically results in a change in all of the universes.

Or at least it should.

The World Turned Upside Down

In Acts 17, we read the following concerning Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica:

The next day, they journeyed through Amphipolis and Apollonia and arrived at Thessalonica. Here, Paul entered a synagogue of the Jews, following his usual custom. On three Sabbath days, he argued with them from the scriptures, explaining and quoting passages to prove the necessity for the death of Christ and his rising again from the dead. “This Jesus whom I am proclaiming to you,” he concluded, “is God’s Christ!” Some of them were convinced and threw in their lot with Paul and Silas, and they were joined by a great many believing Greeks and a considerable number of influential women. But the Jews, in a fury of jealousy, got hold of some of the unprincipled loungers of the marketplace, gathered a crowd together, and set the city in an uproar. Then they attacked Jason’s house in an attempt to bring Paul and Silas out before the people. When they could not find them, they hustled Jason and some of the brothers before the civic authorities, shouting, “These are the men who have turned the world upside down and have now come here, and Jason has taken them into his house. What is more, all these men act against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king called Jesus!” (Acts 17:1-9, J. B. Phillips).

The complaint against the first apostles was not simply that they proclaimed Jesus the Messiah of Israel. That would not necessarily have turned the Roman world upside down. after all, Pilate put up a sign reading, “King of the Jews” on Jesus’ Cross. He did not seem a bit threatened by the claim.

The message that Jesus of Nazareth was a universal Messiah whose salvation was for everyone, in every place, and among every ethnicity was what turned the world upside down. This Messiah was to be the name above all other names, and all secular authorities must bow under his authority, even the Emperor (Philippians 2:10-11). This is the claim that provoked opposition, then and now.

Many commentators have noticed that this proclamation had political and religious significance. Up to that time, political leaders were apt to believe their authority was absolute. that time, political leaders were apt to think of themselves as gods. They often thought of their authority as ultimate. In Jesus Messiah, that claim disappeared. Caesar’s claim to be a god was a false claim. The God of Israel was the one true God. Caesar’s claim to be the ultimate authority on this earth was false. Jesus Christ was the ultimate authority on this earth. If the apostles’ claims were true, then the foundation of the Roman Empire and many empires before that time was undermined.

Our World Turned Upside Down

The same is true today. If Jesus is the true Messiah, and if God’s nature was fully disclosed on the cross, if God really is love, then many of our presuppositions must change. Power is not absolute. Governmental power is not simply a matter of a winner-take-all contest. Our conversion to Jesus Christ changes everything. We can’t believe in the golden rule, “he has the gold rules.” We can’t believe that “Might means right.” We can’t think anything we do is justified because “The end justifies the means.”

Our conversion to Jesus Christ changes everything—or it was intended to. We can resist this change, and many of us do—all of us do at some point in our lives. We refuse to change the way we think, do business, relate to our spouses and family, and relate to others in our churches. We can also refuse to change how we view our culture, its institutions, and others in our society. When we do this, we deny the power of the gospel and the gospel itself. We refuse to change the way we treat people in our churches. Refusals indicate that we are not being converted as we should be. When we do this, we are refusing to allow God by the Holy Spirit to change us in our entire being. We deny both the power of the gospel and the gospel itself.

Copyright 2024, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Donald L. Gelpi, The Gracing of Human Experience: Rethinking the Relationship between Nature and Grace (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2001). Gelpi, a distinguished Jesuit scholar at the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley from 1973 until his death, was a well-known Catholic author. In particular, he was an expert on the thoughts of C.S. Peirce, Josiah Royce, William James, John Dewey, and other pragmatists. My friend thought that I would profit from reading this book. Gilpi is a difficult author to read because he works in the twilight zone between philosophy and theology constantly moving between both disciplines.