Preparation for Resistance

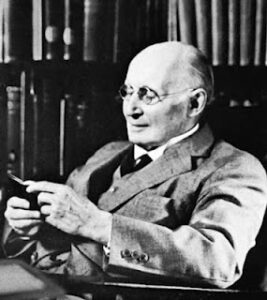

By the time of the emergence of Hitler and the National Socialist Party, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a well-educated Christian with a good family background, trained as a theologian, ordained as a pastor, active in the Ecumenical Movement, and a member of the Lutheran Church of Germany. Every aspect of his development was important in his development as a leader of the Confessing Church movement that opposed Hitler’s policies regarding the church in Germany and later in opposing Hitler’s regime. In fact, Bonhoeffer seems to have had an instinctive understanding of the dangers that Hitler and the Nazi Party held for Germany.

By the time of the emergence of Hitler and the National Socialist Party, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a well-educated Christian with a good family background, trained as a theologian, ordained as a pastor, active in the Ecumenical Movement, and a member of the Lutheran Church of Germany. Every aspect of his development was important in his development as a leader of the Confessing Church movement that opposed Hitler’s policies regarding the church in Germany and later in opposing Hitler’s regime. In fact, Bonhoeffer seems to have had an instinctive understanding of the dangers that Hitler and the Nazi Party held for Germany.

As a theologian, he was familiar with the Lutheran “Two Orders of Government” doctrine. Luther followed Augustine in holding that secular government was a part of the “Order of Creation,” responsible for temporal affairs, while the Church was part of the “Order of Grace,” responsible for the spiritual life of its members. [1] According to this view, the State is necessary because of the Fall, which resulted in humankind needing coercion in order for law and order to be maintained and human society to flourish. Nevertheless, governments and leaders are themselves always morally ambiguous, since they are corrupted by the sin that infects all human institutions and wield the power of the sword, able to compel obedience by force as opposed to invoking obedience by the power of truth and justice. This Augustinian/Lutheran insight and the problems it entails stand at the basis of Bonhoeffer’s political thought.

Order of Preservation

The emergence of Nazism forced Bonhoeffer to reevaluate Luther’s categories, and early on he preferred to speak of “Order of Preservation” as opposed to “Order of Creation” with respect to governmental authority and responsibility. The term “Order of Preservation” emphasizes the role of government to preserve human life and to make possible peace and human flourishing and implicitly places limitations on government and the use of the power of the sword. In his view, Hitler’s Germany was not properly conducting its role as it was destroying and alienating life, not preserving and protecting it. Thus, the young Bonhoeffer writes:

The broken character of the order of peace is expressed in the fact that the peace is expressed in the fact that the peace commanded by God has two limits, first the truth and secondly justice. There can only be a community of peace when it does not rest on lies and on injustice. Where a community of peace endangers or chokes truth and justice, the community of peace must be broken and battle joined. [2]

From the beginning, Bonhoeffer was aware of the evil potential of the Nazi regime and the need to resist Nazi ideology, wherever the truth was being compromised and injustice instituted as state policy. In this quotation one sees the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr on Bonhoeffer’s thought. If truth, morality, and justice are ignored or subverted by a government the fundamental peace intended by God, and therefore the duty of obedience to the state cannot be legitimately enforced by the state on any theological grounds.

The Aryan Clause

The first example of the evil of the Nazi state involved the introduction of the so-called “Aryan Clauses” that restricted the Jewish population of Germany in particular it restricted those of Jewish blood from church leadership. Bonhoeffer immediately saw the evil in this. In his first work against the Nazi’s he wrote:

Thus even today, in the Jewish question, it cannot address the state directly and demand of it some specific action of a different nature. But that does not mean that it lets political action slip by disinterest; it can and should, precisely because it does not moralize in individual instances constantly ask the state whether its action can be justified as legitimate actions of the state, i.e. as actions that create law and order, not lawlessness and disorder. [3]

Even at this early stage, Bonhoeffer is both working within the historic “Two Kingdoms” division of Luther, but is also at the same time preserving the right of the Church and its members to hold the state accountable for its stewardship of the divine task it has been given. Finally, Bonhoeffer is struggling his way forward from inherited theological categories that do not fit the current situation.

Fundamentally, Bonhoeffer clearly saw that the German government had a responsibility to work for the good of all of its citizens, Jews and Gentiles, Aryans and Non-Aryans alike. Where the state failed to do this, it was failing as a preserver of life, justice, and social peace. In other words, Bonhoeffer is working from a Judeo-Christian notion that governments should serve the interests of the people. Implicit in this insight is the insight that a government that was acting against the preservation of its citizens, needed to be replaced by one that would.

Social Critique and the German Christians.

From the beginning, Bonhoeffer believed that the primary role of the church was to bring to bear historic Christian theology upon the issues of his day. “The preaching of the church is therefore necessarily “political,” i.e. it is directed at the order of politics in which the human race is engaged.” [4] Early in the Nazi Regime, Hitler and others began a process of subordinating the church to the ideology and control of the Third Reich. This effort began with the creation of the the German Christian Faith Movement (1932), which was anti-Semitic and involved importing into the Christian faith elements of Aryan influenced neo-paganism. Similar to some efforts today, the German Christians downgraded the importance and authority of the Old Testament and of the letters of Paul because of their Jewish authorship. As a participant in the Ecumenical movement and as a member of the Confessing Church community, his primary focus was theological. His initial resistance was purely against the German Christian movement and its theological errors. [5]

In 1933, the Nazi government succeeded in merging the Protestant churches of the various German federal states and creating the German Evangelical Church. In order to solidify their control, that same year a “German Christian” candidate, Ludwig Müller, was elected to the leadership of the church as Reichsbischof (“Reich Bishop”). The movement acceded to the Nazi definition of a Jew based on the religion of his or her grandparents. Thus, many practicing Christians whose families had converted a generation before were defined as Jews and excluded from the church.

Bonhoeffer saw several theological problems with the German Christian movement. First of all, since the earliest days of the church when confronted with Marcion’s heresy, Christians had accepted the full canonical status of the Old Testament, as part of the witness to Christ. [6] Second, the exclusion of the Old Testament by German Christians as authoritative was not motivated by theological concerns but by anti-Semitism, which Bonhoeffer viewed as immoral and contrary to the Christian ethic of love. Third, the goal of the German Christian theological efforts was political not theological and involved the church supporting a secular ideology antithetical to Christian faith. This led to his final critique, which is that this effort resulted in a heretical, neo-pagan faith. In Bonhoeffer’s view, the German Christian movement and its leadership of the Protestant churches of Germany rendered those churches fundamentally suspect.

Nazi Leadership Principle

Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on January 20,1933. Bonhoeffer was one of the first to protest and oppose the regime in a broadcast of February 1, 19933—a broadcast that was cut short by the governmental censors. [7]This broadcast was directly opposed to the “Leadership Principle” advocated by the Nazi Party, vesting Hitler with almost unlimited powers and responsibilities to achieve the social good of Germany, even at the expense of the family, the church, and other mediating institutions. In this address, Bonhoeffer began by looking at the generational changes that had taken place in Germany since the First World War, changes that led directly to the emergence of the Nazi party and Hitler with his “Leadership Principle.” In the end, Bonhoeffer believed that the results of the First World War, the reparations demanded of Germany by the victorious allies, the depression and other factors had created a generation that had experienced a complete collapse of the very foundations of the society in which they lived. [8]

The result, Bonhoeffer believed was the emergence of a generation who did not “see reality as it is, they do not even reflect on what it can be, but see it as it should be. They naively regard it as capable of any development and transformation and they see it as the elements of a kingdom of God on earth now in the process of realization.” [9] In other words, the cultural realities of Germany between the two wars had allowed the creation of a generation that naively failed to recognize the limitations of the state or any leader, thus making Hitler possible.

In seeking an illusory “kingdom of God on earth” Bonhoeffer believed that the German people had become seduced by a notion of leadership divorced from the kinds of checks and balances that wisdom and a love of freedom urge upon people”

One thing is above all characteristic of this new form (of leadership): whereas earlier leadership was expressed in the position of the teacher, the statesman, the father, in other words in given orders and offices, now the leader has become an independent figure. The leader is completely divorced from any office; he is essentially and only the leader. What does this signify? Whereas leadership earlier rested on commitment, now it rests on choice. [10]

Bonhoeffer saw that Hitler as Fuehrer, with the Nazi “leadership principle” as its theoretical base cut off leadership from any of the roles, duties, obligations and offices that restrict the actions of a leader. The result was that the nation and its population became the servant of the whims of a leader empowered to govern as he or she chose. Bonhoeffer believed this secular notion of leadership put the state and the leader in the place of God, which is contrary to both common sense and the religious idea that even the greatest secular leader is subject to God. It is almost inevitable that a leader acts unwisely and immorally if cut off from that structure of responsibility and servanthood that a democratic society requires.[11] Bonhoeffer believed that the Nazi Leadership Principle and its embodiment in the Fuehrer abrogated the Order of Creation and Order of Grace and placed the leader in an inhuman, uncontrolled and godlike position that no human being should have or possess.

Conclusion

By the time Hitler rose to power, Bonhoeffer was in possession of the theological insight necessary to effectively critique the Nazi ideology and its excesses. He was also well positioned as a respected figure in the ecumenical movement to have a voice not just in Germany but also overseas to lead a resistance against the regime. Next week, we shall review his work in creating and giving a theological structure to the Confessing Church movement as it developed a theological opposition to Hitlerism.

By the time Hitler rose to power, Bonhoeffer was in possession of the theological insight necessary to effectively critique the Nazi ideology and its excesses. He was also well positioned as a respected figure in the ecumenical movement to have a voice not just in Germany but also overseas to lead a resistance against the regime. Next week, we shall review his work in creating and giving a theological structure to the Confessing Church movement as it developed a theological opposition to Hitlerism.

Copyright 2022, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Luther divided human institutions into three basic categories: the household [oeconomiam], the government [politiam], and the church [ecclesiam]. See, Oswald Bayer, “Nature and Institution: Luther’s Doctrine of Three Orders” https://wp.cune.edu/twokingdoms2/files/2016/06/Oswald-Bayer-on-Luthers-Doctrine-of-the-Three-Orders.pdf (downloaded, August 19, 2022).

[2] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, No Rusty Swords: Letters, Lectures and Notes from the Collected Works (Cleveland, OH: Fount Books, 1958), at 154. This work is hereinafter referred to as “No Rusty Swords”.

[3] No Rusty Swords, 219.

[4] No Rusty Swords, “What is the Church” (1932). I have substituted “human race” for “men” in the quote, which is what I believe Bonhoeffer intended.

[5] No Rusty Swords, “A Theological Basis for the World Alliance” (July 1932). In this and other works, Bonhoeffer displays a kind of biblical realism, using the Bible and confessional theology to call the secular state to accountability.

[6] Marcion believed that the Old Testament Scriptures were not authoritative for Christians and denied that the God of the Old Testament was the same God presented in the New Testament.

[7] No Rusty Swords, “The Leader and the Individual in the Younger Generation” (1933), at 187-200. In this, I think that there are similarities between that generation of Germany and that of the United States after the Viet Nam War and other social and political upheavals of the last forty hears of the 20th Century and first twenty years of the 21st Century.

[8] Id, at 189.

[9] Id, at 189.

[10] Id, at 191.

[11] Id, at 195-199. I am summarizing and hopefully clarifying a long argument in which Bonhoeffer critiques the leadership principle as unbounded by the structures of responsibility that are inherent in the view that there are orders of life that give meaning and purpose to human life, and it is the responsibility of government to respect those orders and serve them.