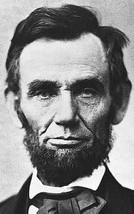

This week is Thanksgiving Week, and in celebration of that event, we are looking at one of the most important of Thanksgiving Proclamations. On October 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued a Thanksgiving Proclamation. It begins:

This week is Thanksgiving Week, and in celebration of that event, we are looking at one of the most important of Thanksgiving Proclamations. On October 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued a Thanksgiving Proclamation. It begins:

The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God. [1]

It might seem odd that Lincoln thanked God in the midst of the tragedy of civil war. The year 1863, however, marked the turning point of the American Civil War. The year began with the President finally, and after much thought, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves. Grounded by Lincoln in his powers as Commander in Chief, it was limited to slaves in the rebellious areas of the nation and read in part:

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons. [2]

The proclamation was intended to free the slaves, give moral authority to the armies of the North, and to encourage an early end to hostilities. However, the freedom proclaimed would be won on the field of battle.

The previous July, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and Vicksburg, Mississippi, the Union troops finally achieved long-awaited victories, which marked the beginning of the end of the Confederacy. In the victorious general at Vicksburg, Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln finally found the leader his armies needed to roll over the talents of Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. The war would drag on another year and a half, and bloody battles would be fought, but the South would never recover from their losses in mid-1863.

Run-Up to the Civil War:

The years following the presidency of Andrew Jackson saw the gradual emergence of the question of slavery as an insolvable national problem. In the North, the economy was not dependent upon slave labor, but in the South it was. In addition, as de Tocqueville pointed out, the solution available in the North to the race issue was not available in the South. This led to a long period of intense conflict and political attempts to mediate the problem.

In 1820, Congress enacted what came to be known as the “Missouri Compromise.” In that year, Missouri was admitted to the Union (the first state West of the Mississippi River) as a slave state while Maine was admitted to the Union as a free state, maintaining a delicate balance of political power between the North and South. The Missouri Compromise also banned slavery in lands which had been a part of the Louisiana Purchase north of 36º 30’ which was roughly the southern boundary of Missouri.

Thomas Jefferson, who was still alive at the time, felt the compromise would not work and could lead to Civil War. His fears turned out to be well-grounded. The Missouri Compromise maintained a temporary peace, but failed to resolve the moral problem of slavery. In addition, it created a deep division between the North and the South—and a line which with the earlier the Mason Dixon Line that might demark the boundaries of a divided United States of America. [3]

Congress continued to attempt to find ways to maintain the Union by compromise. California was admitted to the Union with a requirement that one of her Senators be pro-slavery. In 1854, the Missouri Compromise was abandoned in the “Kansas and Nebraska Act” was passed, allowing slavery in a region north of the 36º 30’ line. Passage resulted in violence between pro- and anti-slavery factions.

In 1857, under the leadership of Roger B. Taney, the Supreme Court decided Dred Scott v. Sanford ruling that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional holding that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories, as the Fifth Amendment guaranteed slave owners could not be deprived of their property without due process of law. [4] This meant that there could be no legislative or judicial path out of the difficulties of the union caused by slavery. For the probem of slavery to be resolved, an amendment to the Constitution would be required—an unlikely event. In my view, with the Dred Scott decision, the only path left to resolve the issue of slavery was war, which erupted four years later with the election of Abraham Lincoln as President.

In the wake of the Kansas Nebraska Act, a little-known lawyer from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, ran against Stephen Douglas, the Senator who spearhead passage of the Kansas Nebraska Act. This election produced the famous, “Lincoln Douglas Debates.” Douglas won the election; however. historians judge he lost the debates—and in the process brought Abraham Lincoln, an obscure politician and lawyer to public prominence. In the election of 1863, Lincoln was the candidate of the Republican Party for President and won. He was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, and war commenced on April 12, 1861 when confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina. [5]

The years preceding the Civil War demonstrated a failure of the American political system to end slavery peacefully. All the institutions of government, congressional, judicial, and executive failed in their duty to find a way to end slavery. Every attempt at compromise failed, because no compromise was possible with respect to so great an evil. In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln urged a compromise and patience in resolving the issue of slavery, but that was not to be. [6] The future of the nation was to be determined on the battlefield.

President Lincoln and the First Months of the War

When Lincoln was elected President, southern states were already in the process of separating from the Union. His life was in danger. In his First Inaugural Address, the careful lawyer was on display and certain features of his leadership were evident. The speech foreshadowed the leadership he would give and the greatness he would achieve.

His appeal to the South was simple: Nothing had changed. The South was under no immediate need to separate from the Union, and no southern state had any obligation to leave the Union. Lincoln, on the other hand, had sworn an oath to “faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” He was warning the South that he would be compelled to take up arms to defend the union, a principle that defined his presidency. Nevertheless, the Confederacy was formed, and Ft. Sumpter attached in April of 1861. From that time forward it was clear that the fate of the Union would be decided on the field of battle.

In the first year and a half of the war, Lincoln was hampered by a series of commanding officers of the Army of the Potomac, who were either not competent, excessively cautious, outfoxed by the Commanding Officer of the Army of Northern Virginia, or hostile to his leadership. General Robert E. Lee had been offered command of the Union armies at the outbreak of the war, but had felt loyalty to his home state of Virginia must come first. He proved to be an able general, especially in turning defensive situations into offensive possibilities. His victories in the early years of the war despite being out-manned and out-gunned were and are legendary.

It is often forgotten that Lincoln was made fun of by the press of his day and not admired by many in Washington. His first years in office were challenging, and his greatness was unrecognized. In spite of all this, he stayed the course. At the same time, the industrial might of the North was growing, its army increasing in size and capacity, and wearing down the army of the Confederacy, which was an agrarian area of the nation, lacking in the industrial potential to wage the kind of war that was emerging during the period of the Civil War.

Despite setbacks, by the summer of 1863 the South needed a victory which would force a peace process satisfactory to the Southern states. Otherwise, Lee knew the armies of the Confederacy ultimately would be overwhelmed. Lee devised a plan to invade Pennsylvania without the aid of his greatest lieutenant, General Thomas Stonewall Jackson, who had died as a result of friendly-fire injuries the previous may in the Battle of Chancellorsville. General Meade proved an able and competent opponent, and Lee lost the Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the war.

Thanksgiving 1863 and Lincoln as a Theologian of Politics

So it is that President Lincoln felt that the nation should thank God for the blessings of the year past. Therefore, in October, he issued this call for a National Day of Thanksgiving:

The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God. In the midst of a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union. Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defence, have not arrested the plough, the shuttle or the ship; the axe has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom. No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy. It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity and Union. [7]

There are features of this proclamation that appear in other works by Lincoln, and which reveal him as a profoundly religious person, with a religious attitude towards the situation of the nation. Lincoln recognizes the blessings of life even in the midst of conflict. He sees the fragility of the human condition and need for the grace of the Almighty Most High God. He sees the Civil War as, in some way, a punishment for national sin, and especially the sin of slavery, an attitude he also reveals in his Second Inaugural Address. [8] He saw the magnitude and severity of the war as commensurate with the evil being addressed.

Lincoln, however, does not see himself or the Union as avenging angels, but as instruments of God in order that the slavery might end, the wounds of the war healed, and peace and harmony restored. Whatever the current state of the Union and his own and our national suffering, a Beneficent God was at work for good in the struggles of the Civil War. For himself and the nation, the proper response was a humble thankfulness for such blessings as had been received, repentance for the flaws that were the cause of the suffering, and a prayer for mercy and the return of peace.

Conclusion

This Thanksgiving 2021, as we hear so many strident voices from the left and the right, and the harsh voices of deluded souls captured by a “Politics of War” attempt to inflame our natural prejudices and failings, perhaps we might listen to the final counsel of our unique “Theologian of American Anguish,” [9] Abraham Lincoln:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan–to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations. [10]

Copyright 2021, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] See, “Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving” at the American Battlefields Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/abraham-lincolns-proclamation-thanksgiving?ms=googlepaid&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIspT0peuf9AIVZnxvBB1AdAhPEAAYASAAEgJX9_D_BwE (downloaded November 17, 2021).

[2] See, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation January 1, 1863 at the American Battlefields Trust,https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/abraham-lincolns-emancipation-proclamation?ms=googlepaid&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_8W4ru6f9AIVESM4Ch1rKQvEEAAYASAAEgJ4X_D_BwE (downloaded November 17, 2021). The proclamation excluded the then union occupied areas of except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans.

[3] Although a footnote to the history, the term “Mason Dixon Line” was used as a part of the language of the Missouri Compromise, referring to an earlier dispute between the between the British colonies (now states) of Maryland and Pennsylvania/Delaware. In popular terminology it refers to the cultural line between the Northern and Southern parts of the United States.

[4] Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

[5] In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln attempted to pacify the southern states, which were in the process of leaving the union, urging a constitutional and legal resolution to the problem. This, like all previous attempts at compromise, failed. Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (March 4, 1861).

[6] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address,” previously cited.

[7] Abraham Lincoln, “Thanksgiving Proclamation” (October 3, 1863).

[8] Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” (March 4, 1865).

[9] The title of this week’s blog comes from a wonderful little book by Elton Trueblood, Abraham Lincoln: Theologian of American Anguish (New York, NY: Harper One, 1973).

[10] Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address (March 4, 18650>