July 4th is Independence Day. I am writing this on July 3, a day Americans seldom remember, but it is when the battle of Gettysburg ended. The action commenced on July 1, 1865, and ended on July 3. When the Confederate Army left the battlefield, they did not know it, but the “High Tide” of the Confederacy had been reached, and the war was now lost. What remained now was the slow march that would end at Appomattox Courthouse in April of 1865. In the meantime, many fine young men would die.

July 4th is Independence Day. I am writing this on July 3, a day Americans seldom remember, but it is when the battle of Gettysburg ended. The action commenced on July 1, 1865, and ended on July 3. When the Confederate Army left the battlefield, they did not know it, but the “High Tide” of the Confederacy had been reached, and the war was now lost. What remained now was the slow march that would end at Appomattox Courthouse in April of 1865. In the meantime, many fine young men would die.

General Lee, who commanded the Army of Northern Virginia, knew that the Confederacy could not win a war of attrition, nor could his commanders win battles forever against an increasingly dominant foe by the sheer brilliance of strategy and the energy of commanders in the field. The invasion of Pennsylvania was an attempt to force a negotiated settlement. Gettysburg was not Lee’s chosen site for the battle. It is simply where the two armies met.

The site, however, favored the Army of the Potomac and its new commanding officer, General George Meade. He had replaced General Joseph Hooker, whom Lincoln did not think was aggressive or wise enough to win the battle. (Hooker’s personal and leadership morals gave us the phrase “Hooker” for a certain sort of woman that followed his army.) For three days, the battle raged. Lee was hampered by the death of Stonewall Jackson, his best commander, and J. E. B. Stuart, his cavalry commander, did not arrive as anticipated and left the old warrior blind to the enemy movements until it was too late. Finally, Lee was sick, probably with a mild heart attack. He was not at the top of his game.

During the battle, Lee uncharacteristically made three errors: (1) he over-estimated the capacity of his army, (2) he underestimated the strength and tactical advantages of his opponent, and (3) he fought the battle with insufficient information due to the failure of Stuart to arrive in a timely manner. Lee’s health unquestionably impacted his judgment. He was ill for most of the battle. Nevertheless, his concern for his army and the battle’s fairness was undiminished. He warned his soldiers against bad behavior despite the fact that they were in the enemy’s heartland, not Virginia.

On the other hand, Meade was competent, brave, and not easily rattled, a characteristic too common among Union Generals up to this point in the war. One commentator puts it this way: Meade deployed his forces effectively; relied on capable subordinates to make decisions where and when they were needed; took great advantage of defensive positions; wisely shifted defensive resources on interior lines to parry strong threats; and, unlike some of his predecessors, stood his ground throughout the battle in the face of fierce Confederate attacks [1]

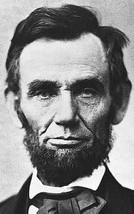

Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the costliest single day in our nation’s military history. Reflecting on the battle, Lincoln summed it up in words that should never be forgotten:

“But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. “[2]

“But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. “[2]

In every war, someone loses, and someone wins. Lincoln’s genius was that he could speak words that applied to the winners and losers, to all that loved their country, which is why after the war was over, both sides could see in his address the profound wisdom and love for all that inspired them.

I have quoted these words in the past on July 4th. This year, I want to take our attention back to the words that preceded them:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. [3]

Most unfortunately, we and our leaders, in the quest for power and for the creation of a nation in the image we feel best, have allowed our country’s dedication to the liberty of all to degenerate into a civil war of a kind. We sometimes call it a “Culture War.” I believe that a good portion of that war is deliberately fought to distract the public from the reality that their freedom and way of life are being taken from them by oligarchs, corrupt politicians, intellectuals, and a host of “opinion makers” left and right. We are not “met on a battlefield” of a battle past, we are on the battlefield.

It is easy to lose perspective during a battle. It is easy to forget that the folks on the other side are just as dedicated and just as sure that God (or my least favorite term, “history”) is on their side as we are confident of the righteousness of our cause. It is easy to forget that God loves everyone, including those we believe to be fundamentally wrong. It is easy to say and do things we will regret when we lie a few seconds from death.

At such times, it is a good idea to remember the ending of the Gettysburg Address, “…we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” It is on days like today that we need to renew a certain basic resolve that we who are here today wish to leave to our children and grandchildren, all of them, of whatever race, color, creed, or political view, the benefits of the freedoms and prosperity we enjoy.

We did not create this land. We inherited it. We inherited it as a gift the day we came or were born. Those who lived before us built the nation with their blood, sweat, toil, and tears. They worked in good times and depressions, in peace and war, in plenty, and in want to build the country we inhabit. We are not its owners. We are trustees for those who will come after us.

On October 17, 1863, the Civil War was not over. Another bloody season lay ahead. I am afraid that a different kind of bloody season is ahead for us all. The question boils down to this: Will we fight with the tools of reason, love, mutual forgiveness, forbearing differences, and forgiving mistakes, or will we fight until someone wins and everyone else loses? There lies the question before us.

Happy Independence Day!!

Copyright 2023, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Murray, Williamson and Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh. A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016) at 285, found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gettysburg6 (downloaded July 3, 2023).

[2] Abraham Lincloln, Gettysburg Address (October 17, 1863).

[3] Id.