Sometimes, even our most well-intentioned actions have negative consequences. Leaders often make decisions in good conscience but without a complete understanding of the costs of their choices. Usually, leaders are given good advice, which has unforeseen results. Stress, failure, opposition, and other negative experiences are part of the life of every human being and every Christian leader.

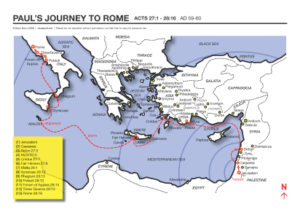

We began the prelude to Paul’s eventual trip to Rome two weeks ago. He had been warned that his travel to Jerusalem would result in danger, and those who prophesied from the danger were correct. Almost immediately upon his arrival and travel to the temple in Jerusalem, he is recognized and provokes a violent response.  Paul’s defense of his ministry in the Temple courts provoked a riot so severe that the Roman legionnaire in charge felt it necessary to intervene (Acts 22). Paul went to the temple to obey the suggestions of the Christian church leaders in Jerusalem. He was trying to do the right thing. However, the consequences were not what anyone had anticipated. However, he was able to defend his ministry. Even that did not go well.

Paul’s defense of his ministry in the Temple courts provoked a riot so severe that the Roman legionnaire in charge felt it necessary to intervene (Acts 22). Paul went to the temple to obey the suggestions of the Christian church leaders in Jerusalem. He was trying to do the right thing. However, the consequences were not what anyone had anticipated. However, he was able to defend his ministry. Even that did not go well.

The Religious Nature of the Conflict between Paul and the Jewish Leaders

Near the end of his address to the crowd, Paul brings up the resurrection, which the Pharisees believed in, but the Sadducees did not. This provoked an additional conflict. Remembering that Luke probably wrote hacks partially as a defense of Paul, a defense that would be presented in Rome, this little vignette gives us an insight into one line of defense that Paul had against the charges against him. The Roman Empire allowed much religious diversity, and Roman governors did not interject themselves into disputes between religious sects. They were especially familiar with the violent disagreement among the Jews about religious matters, including the resurrection. By adding this vignette, Luke provides a defense for Paul in front of the emperor: the charges brought against Paul by the Jews were simply matters of religious dispute among Jews and not a matter of Roman law or threats to the Roman state.

The text indicates that Luke is defending Paul before the Roman Emperor. While he was under arrest in Jerusalem, the Lord Jesus appeared to him, saying, “Take courage! As you have testified about me in Jerusalem, so you must also testify in Rome” (Acts 23:11). Neither Paul nor Luke felt that Paul’s imprisonment and trial in Rome were in any way unusual; they were part of God’s plan.

Transfer to Caesarea

Paul’s appearance at the temple provokes not just a violent response of immediate anger but also a conspiracy to put Paul to death (23:15). The potential for religious beliefs to result in violence is not only an ancient phenomenon. Sadly, for all religious groups, the existence of religious violence and religiously motivated violence is, for most people, a strong argument against the value of religion. The response of a small number of Jewish people is a reminder to all of us that there is a limit to what should be done to defend one’s religious beliefs. In the case of Christians, the fact that God is love and does not desire anyone to suffer violence adds additional emphasis to the importance of respecting other peoples, religious beliefs, and their right to disagree with ours.

Fortunately, a relative of Paul became aware of the plot against Paul’s life (v. 16). When Paul learned of the plot, he informed the centurion, who made arrangements for Paul to be transferred to Caesarea, where Governor Felix had his headquarters (v. 19-23). To fully inform the governor, the officer sent Paul a letter informing him of the situation and his handling of the problem (vv. 25-30). Thus, another step is taken, bringing Paul closer to his goal of eventually visiting Rome.

Trial before Felix

Five days after Paul was taken to Caesarea, the High Priest, the elders, and their lawyer came down from Jerusalem to give evidence against Paul (24:1). Tertulius, their lawyer, accused Paul of being a troublemaker and a desecrator of the temple (vv. 2-9). Paul, who had heard of Felix, was more than willing to give his defense. It began by explaining that he had only been in Israel for a brief time. He admitted that he was a follower of the way who worshiped the God of Israel, believed in all things taught in the law and the prophets, but who believed that Jesus was the foretold Messiah and the fulfillment of the Jewish Hope of a resurrection from the dead (vv. 9-14).

Paul went out to explain that he had been absent from Israel and Jerusalem for some time. He, therefore, came to bring arms and offerings for the people of Israel. While there, he had been in the Temple courts purifying himself. He was not with a mob of people but only a few colleagues (vv. 17-21).

At this point, Paul made an important statement for his defense. He claimed he had done nothing wrong and said nothing that caused anyone any trouble except perhaps one statement: his belief in the resurrection of the dead of Jesus Christ. This was an extremely wise move on Paul’s part. The Pharisees believed in a resurrection, while the Sadducees did not. In addition, Roman law gave a great deal of freedom to religious beliefs. This was particularly true for the Jewish people because the Romans were well aware of their tendency to engage in disputes that could become violent. It was Roman policy not to interfere with private religious conflicts. Paul’s statement was designed to show that this was his case. All of the trouble that had been caused in the temple was not because of any revolutionary act by Paul or any failure to abide by Roman or even Jewish law but only because of a religious belief (v. 21).

At this point, Felix seems to have seen a way out of the predicament. He immediately called a halt to the proceedings and delayed the hearing. In other words, Felix was not only buying for time but also giving Paul a chance to prove his allegations were true. Also, it’s possible that he was hoping that Paul would give him some kind of a bribe to rule in his favor, which he was probably inclined to do in any case (v. 26). As a point of history, Felix did have a bad reputation for minor corruption of a financial nature. Whatever the case, Paul was left in house arrest for two years (v. v. 27).

Those two years of enforced solitude and inactivity were stressful for Paul. Nevertheless, it’s very possible that there was a positive side to the delay. Many scholars think it was during this period that Luke did the research that would ultimately result in the gospel of Luke. For example, during this time, he may have interviewed Mary and others and gathered the information he needed for the birth narratives of the story. Perhaps during this time, he had a chance to look at collections of the sayings of Jesus and begin to outline his ideas about the book he intended to write.

This is a reminder to all of us that sometimes delay, and even long delay can be a positive experience in God’s providence. We may want to undertake a new task, begin a new ministry, or start a new career. All these things may take study, planning, and quiet solitude to bring to fruition. God sometimes brings space into our lives amid trouble so we might grow and develop the capacities needed to undertake the next chapter of our lives.

Paul’s Defense before Festus

Eventually, Felix was replaced by Festus, and it was time to take care of delayed business. Once again, the High Priest and those who wanted to accuse Paul came before the governor and asked that Paul be brought to trial (25:1-2). It so happened that Festus was about to go to Caesarea and suggested that the trial be held there. He may also have been concerned about Paul’s safety, having heard the rumors of attempts on his life. It was that Paul was brought before the new governor. Once again, Paul’s defense is essentially that he has not done anything to violate the law of the Jews, Temple laws, or Roman law (v. 8-9).

Festus, trying to get off on a good start with the Jewish people, asked Paul whether or not he would be willing to go to Jerusalem to stand trial. It was here that Paul played another legal card. He insisted that he tried in Caesarea and appealed to Caesar. Paul was a Roman citizen. Therefore, he had the right to demand a trial before Caesar, and Festus was obligated to grant that request. Whatever happened next, Paul would get a chance to visit Rome – which was his intention all along. In all this, we see both God’s Providence and the apostle’s shrewdness.

Festus recognized that he had a way out. Therefore, he tells Paul, “To Caesar, you have appealed to Caesar, you will go” (v. 12). In a way, all that transpires after this before Paul gets to Rome is commentary because Paul has assured himself that he will get to Rome and be able to defend the Christian faith before the supreme ruler of the Roman Empire. Before another word is said, Paul has actually won.

Nevertheless, Paul has another opportunity to share his testimony. After a while, King Agrippa and his wife, Bernice, visited the new Roman governor. This gave Festus a chance to allow Agrippa, who, after all, was able to understand the religious complexities of the Jewish faith. King Agrippa knew all about Paul and wanted to hear what the apostle had to say. As an aside, Festus notifies Agrippa that he doesn’t think that Paul has done anything to violate Roman law (v. 25). This, Festus believes, creates a problem. It was customary to send a list of charges against someone being transmitted to Rome for trial before Caesar. Festus doesn’t know what to say in this case because he doesn’t see that Paul has committed any crime.

At this point, it might be important to ponder Luke’s motives in including this scene in his narrative. Once again, some scholars believe that the book of Acts is essentially a defense of the apostle Paul. In particular, specific portions may have been written as part of an outline of defense that Paul intended to be made before Caesar. The statement, repeated more than once, that the Roman authorities involved were unclear that Paul had done anything that might be wrong could be put before Caesar as evidence that Paul should be released.

We’re jumping ahead, but many scholars believe that Caesar released Paul, continued his ministry to Spain, returned to Rome, and then was arrested for the final time. This would explain why Acts ends the way it does and why Paul may have had an opportunity to continue his ministry after his arrest in Jerusalem. The Roman authorities involved didn’t think he had done anything wrong. As a practical matter, most likely, Caesar would have followed the advice of his lieutenants unless he felt, for some reason, that they had made a mistake. The book of Acts seems to have been written partially to prove that those who felt Paul had done nothing wrong, or at least nothing violating Roman law, or correct.

Paul’s Defense

Some weeks ago, I wrote a blog outlining the spiritual meeting of Paul’s defense and how it shows how we might defend our faith in our day. In this particular blog, I want to take another tack. What’s evident in the narrative is that when Paul describes what he has been doing, he tries to convince Festus and Agrippa that they should become Christians! At one point, Agrippa responds to Paul, “You almost convince me to become a Christian!” (26: 28).

Paul responds that he does wish that Agrippa would become a Christian (v. 29). Immediately after these explanations, Agrippa and Festus agree that Paul has done nothing deserving death or imprisonment (v. 31). In fact, if Paul had not appealed to Cesar, they would have released him 9v. 32). Once again, here we have Roman authorities and the Jewish authority over the people of Jerusalem, agreeing together that Paul has done nothing wrong. The agreement between the Roman governor and the Jewish king was that under neither Roman nor Jewish law, Paul was guilty of a crime. This is a solid defense.

What was the content of Paul’s defense? Paul began by giving Festus and Agrippa a brief history of his life. The point of this part of the discussion is that Paul had been a religious Jew all his life. He had been a Pharisee of the strictest sect. Pharisees believe in the resurrection of the dead, and Paul had been a Pharisee who believed in the resurrection of the dead. He did not, however, believe that Jesus was the source of resurrection. Therefore, he persecuted the Christians. He went to such extremes that he persecuted the Christians in Damascus.

In other words, Paul’s description of himself is not very different from his accusers. Like them, he was a Jew. Like them, he was deeply religious. Like the Pharisees, he obeys the law strictly. Like them, he rejected Christ. He then recounts that he had been confronted with a vision of the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. Christ had admonished him about persecuting Christians because in persecuting Christians, he was persecuting the risen Messiah. Christ appeared to Paul because he might become an apostle and messenger of the Christian faith.

In other words, at the beginning of his defense, Paul agrees with the arresting officer, Felix, Festus, and Agrippa, that Paul has done nothing wrong that would involve Roman law. His difficulties with the Jewish authorities are not a dispute about Roman or Jewish law but a disagreement about whether or not the resurrection of the dead is a valid doctrine and whether or not Jesus of Nazareth was the fulfillment of the resurrection hope of the Jewish people. If Paul was correct (and he was), Paul had done nothing wrong under Roman law.

Conclusion

Next week, I hope to conclude this little series of blogs. I’ve tried to show this week that the book of Acts is not simply dictated off the top of Dr. Luke’s head with no purpose in mind. In fact, throughout the book, it has been researched and has a purpose. One of those purposes is to defend the ministry of Paul. I think it is quite possible that the latter part of the book was written partially to be read in some form to the Roman emperor in defense of Paul’s ministry.

We sometimes underestimate Christians’ need to be wise, study hard, and be careful what we say and how we say it. We are called to defend our faith. Christ warned us that we will occasionally be called before important people to make that defense. When that happens, we need to be wise. From the beginning, Paul shows a certain shrewd wisdom in how he handles his defense. He conducts himself in a dignified manner. He provides his accusers with the best possible defense against the charges against him. This defense, which is ultimately pretty simple, is often missed by contemporary Christians. What Paul is saying is that the religious dispute between him and the Jewish people is not a matter for secular authorities to handle.

This posting is a rework of a prior blog and sermon. It seemed appropriate for the time we were in. I am posting it on New Year’s Eve as we say goodbye to 2024 and look forward in hope to 2025.

This posting is a rework of a prior blog and sermon. It seemed appropriate for the time we were in. I am posting it on New Year’s Eve as we say goodbye to 2024 and look forward in hope to 2025. I heard the Bells on Christmas Day ends on this word of Hope:

I heard the Bells on Christmas Day ends on this word of Hope: