The paradigm for visualizing the world and human society envisioned the universe as made up of matter and society as made up of isolated individuals, both of which were bound together by forces. In the realm of industry, this meant technology. In the political sphere, this meant human ingenuity was put into the service of gaining political and economic power. In the thoughts of Hobbes, Rousseau, Marx, and others, there was no inherent limit to the sovereign’s power. In the hands of Nietzsche, this became a recipe for disaster because all that mattered was raw power and the desire to dominate (Will to Power).

The paradigm for visualizing the world and human society envisioned the universe as made up of matter and society as made up of isolated individuals, both of which were bound together by forces. In the realm of industry, this meant technology. In the political sphere, this meant human ingenuity was put into the service of gaining political and economic power. In the thoughts of Hobbes, Rousseau, Marx, and others, there was no inherent limit to the sovereign’s power. In the hands of Nietzsche, this became a recipe for disaster because all that mattered was raw power and the desire to dominate (Will to Power).

American and other political institutions have been powerfully impacted by the Newtonian worldview, a Hobbesian view of politics focused on power and the theoretically unlimited power of the state. Just as under the influence of a mechanical view of the universe, modern thinkers were predisposed to perceive the world as consisting of small units of matter held together or influenced by forces; in politics, this worldview predisposed policy-makers to either extreme individualism or Marxist-influenced communalism, viewing the core governmental forces as power influenced solely by economic factors, all explicable through scientific analysis. Thus, the 20th Century’s most influential political and economic theories: Capitalism and Marxism.

In recent years, a materialistic model of the world has been superseded by a model that assumes deep interconnectedness, relationality, freedom, and inner sensitivity. By the middle of the 20th Century, at least physicists understood that the Newtonian model of the universe was limited and fundamentally incorrect. Today, scientists believe that the world, at its most fundamental level, is composed of disturbances in a wave field, with the result that every aspect of reality is deeply connected with every other aspect. Some scientists even believe that the world is fundamentally composed of information. Whichever view turns out to be correct, the fact remains that matter and forces are not fundamental. In theology, a robust analysis has emerged, suggesting that the world is profoundly interconnected and relationships are more essential than matter or energy. This fundamental view of reality cannot help but impact our view of human beings and society.

The insights of theoretical physics and other academic disciplines into the fundamentally relational nature of reality and the limits of a merely reductive scientific enterprise have been slowly transforming society. A newer “organic model” that sees the universe not as a machine but as an organism or a process is gradually emerging and influencing public life. As the implications of this new worldview are better understood by citizens and politicians alike, political life and the contours of our politics and political institutions are bound to change, hopefully rationally and peacefully.

The modern world is dying, and something new is emerging. What we call “post-modernism” is only the beginning of the change and might be better called “Hyper-Modernism” or “End-stage Modernism.” The descent of modern thought into “hermeneutics of suspicion,” “deconstructionism,” and various forms of nihilism is fundamentally critical reasoning taken to an absurd end. The inevitable result will be that reason, spiritual values, moral imperatives, and the like will reemerge as essential factors in a wise polity. The vision of the purely secular, materially driven, and scientifically managed state will wither away until it finds its proper place in a more comprehensive human polity.

Hopefully, a newer vision of political reality will emerge in its place – a constructive form of postmodernism.“Sophio-agapism” describes the philosophical proposal defended in these essays. Just as the world comprises an intricately intertwined web of reality, governments will recognize that human politics must begin with smaller units, like the family, and move organically into more comprehensive organizational units with essential but limited powers. The vision of the all-powerful nation-state that controls a territory through legal, administrative, and bureaucratic power will be proved inadequate and false. Whether this happens due to a great crisis and collapse of the current nation-state, world-state visions, or organically, through the decisions of wise leaders, depends on the decisions we all make. One thing is for sure: a wise and genuinely post-modern political order will value dialogue as much as debate and decision.

In this series of essays, I’ve tried to discuss historical pragmatism and the development of a particular approach to political life and thought. In the process, I’ve been attempting to sketch out the contours of a sic approach to political theory and life. Briefly, the essential elements are as follows:

A Politics of Wisdom

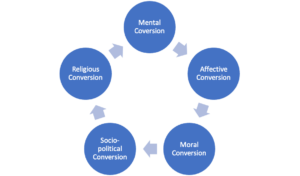

Sophio-agapism embraces the notion that political philosophy and political action can be reasonable (the sophiomove) and serve the common good by understanding a society’s political life, the options for change available, the historical trajectory of that society, and other factors while experimenting wisely among various policy options. This is a turn away from a view of politics as primarily a matter of Will and a return to an older view that politics is mainly a matter of practical wisdom (phronesis). As a form of practical wisdom, sophio-agapism embraces the notion that wisdom comes from experience embedded in the human race’s experience through the ages and from the advances of modern science and technology.

A Politics of Love

Sophio-agapism embraces a communitarian viewpoint that sees all participants in society as part of a common community bound together not just by power but fundamentally by a willingness to sacrifice for the community, whose interests must be considered in addition to the selfish interests of individuals that make up that community (the agapic move). In particular, nurturing families, neighborhoods, mediating institutions, and voluntary societies creates social bonds that give stability and restraint to the state’s power and can accomplish goals that state power alone cannot achieve.

Political love is fundamentally a recognition that society is a joint endeavor requiring the cooperative efforts of all participants to achieve human flourishing. It is a social bond that transcends individual grasping and the search for personal peace, pleasure, and affluence. It requires confidence that the existing social order, as flawed as it may be, provides positive benefits to all members of society and should be protected while at the same time advancing in the realization of justice and human flourishing.

A Focus on Social Harmony

Sophio-agapism embraces the ideal of social harmony as the goal of political life. The modern, revolutionary focus on equality dooms political life to unending conflict among persons and classes. Political life aims to achieve progressively more significant degrees of harmony among the various participants in any society. A return to viewing social harmony as the foundation of wise and just decision-making is implied by the interconnectedness of the world and the various societies humans inhabit. Equality is undoubtedly an essential component of justice, as are opportunities to achieve, the acquisition of property that one can call one’s own, respect for all citizens, and a host of other components of a functional society.

The Reality of Universal Values

Sophio-agapism embraces the recovery in the public life of the notion that critical universal values, like justice, are not merely matters of the will of a majority or the choice of a single individual or ruling class but noetic realities. These noetic realities, what I have called Transcendental Ideals, can be studied, internalized, and applied to practical problems and extended in the dynamic process of the political life of a society. This requires the disciplined, fair, and impartial search for such values and their application in concrete circumstances by all the relevant players in society, private citizens, public officials, policy advisors, etc.

The kind of moral confusion we see in the West is evidence of the need to recover a sense of the reality of ideals, such as justice, and the importance of their continuing enfolding as part of a tradition of moral, political, legal, and philosophical inquiry by communities devoted to the unbiased search for justice. These Transcendental Ideals exist as ever-evolving noetic realities to be progressively revealed by a community dedicated to uncovering their nature and application.

A Wholistic Reason

Sophio-agapism embraces a holistic view of political wisdom and a recovery of classical and modern thought in guiding public policy. This means superseding the dissolving effects of critical reason as the primary source of political thinking and including with critical reason a form of reasoning that involves the cherishing of people and institutions within the political life of a society. In modern political theory, will and power have become dominant factors in public life. Power alone and the Will to Power do not lead to human or social flourishing unless they rest on a substructure of caring for others and institutions.

Politics is not primarily science; it is a skill. The skills involved include the ability to choose among alternatives, forge a consensus, make difficult decisions in solving public problems, maintain the maximum degree of social harmony, and other skills that are not primarily cognitive. In addition, they are not encouraged by the dissolving effects of critical reason. Just as there is a skill beyond technical proficiency in creating a symphony, social harmony is not entirely a matter of technical ability or scientific determination. Polls, for example, can only get you so far in the search for justice.

Fallibility and Limits

Sophio-agapism embraces developing a sense of limits in public life. The historical trajectory of the political development of any society places limits upon wise and caring change. The history of a society and its trajectory also opens avenues for developing the tradition of which that society is a part. The Enlightenment brought about a period of revolutionary thinking, exemplified by the French Revolution and the Marxist revolutions of the 20th Century. The results are not encouraging in the search for either social harmony or human flourishing. Rather than being revolutionary, sophio-agapism is evolutionary. It believes that the gradual evolution of human society guided by human wisdom and love can create a better future over time. Connected with this insight is a resistance to millenarianism of the left or right, Marxist or Capitalist. Humans cannot achieve a perfect society, but humans can improve upon the society in which they live.

Sophio-agapism encourages a sense of limits and a recognition of human fallibility in political life. Not all problems can be solved, and very few can be solved entirely or quickly. The attempt to make massive social changes involves the risk of enormous societal damage. This argues for an incremental approach whenever possible. Not all problems are susceptible to incrementalism, but a great many are. There is the chance of a significant cost and waste if substantial changes are made. It is hard to reverse the damage done by a massive political change. It is much easier to change course when the original action is incremental. This kind of incrementalism is not enhanced by the emotion-driven politics that currently characterizes Western democracies.

Investigation and Dialogue

Embracing an abductive (scientific) and dialectical model of political reasoning and behavior that deliberately attempts to find the best rational solution for all involved, seeking the harmony of society as a whole, and resisting political life’s descent into a form of warfare by other means. Reasonable dialogue is essential for societies to recover a sense of mutual respect for differing opinions and a standard search for the best solution among available options.

Many social problems arise from illogical, emotionally driven, poorly conceived policies. From how many governmental programs are structured to the outcomes permitted to the corruption and waste involved, these programs represent both a failure of character in leadership and a failure of thoughtful reaction to societal needs. The propensity to avoid complex problems until they are dangerously large and politically unavoidable is a risk in any democratic society. When the propensity becomes endemic in all areas of conflict, it is dangerous to political institutions.

Dialogue is important because it allows political actors to accomplish two essential goals in maintaining social harmony: the investigation of alternative policies and proposals and the maintenance of the maximum degree of unity during periods of decision. Contemporary politics is exceptionally reliant upon divisive, simplistic, and polarizing rhetoric. Focus on dialogue and reason would allow political actors to maintain social harmony while investigating the best policy to adopt. It would also allow the political climate to become more harmonious.

Overcoming the Focus on Power

Both political liberals and conservatives agree that there are fundamental problems in society and the human community. Interestingly, it may be a shared fundamental worldview that is at the root of the decay of public institutions. The idea that the world is fundamentally material and that politics is a matter of power and power alone is a profound source of the irrational behavior of the right and the left. If the world is fundamentally rational and relational, then all solutions that flow from a purely materialistic view of society—a view shared by extreme capitalist and socialistic theories of government, lie at the root of many of the problems we face and certainly at the root of an increasingly dysfunctional style of politics. The urgency for a new, more relational rational government ontology is apparent, emphasizing the potential importance of further developing the philosophical perspective outlined in this series of essays.

Copyright 2024, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved