This is my last post for the time being from The Ethics of Beauty. [1] In this particular Blog, I will focus on the relevance of a focus on Beauty for the Great Commission and the Christian endeavors of Evangelism and Discipleship. It turns out that beauty is essential in drawing people into God’s church.

This is my last post for the time being from The Ethics of Beauty. [1] In this particular Blog, I will focus on the relevance of a focus on Beauty for the Great Commission and the Christian endeavors of Evangelism and Discipleship. It turns out that beauty is essential in drawing people into God’s church.

When I was a new Christian, the first books I read were C. S. Lewis’ “Mere Christianity,” Francis Schaeffer’s “The God Who Is There,” and Josh McDowell’s “Evidence that Demands a Verdict.” It sounds as if (as was somewhat the case) that my conversion was a “truth first” conversion. However, there is more to the story.

In a broken part of my life, a woman who worked in a law firm with me invited me to a Bible Study in Houston, Texas, one spring Friday night. Although there were a few singles (one of whom I eventually married), most participants were young married people about my age. Over the next few months, I got to know many of them, had meals in their homes, and saw the difference between their lives and mine. The common denominator for these happy couples was their faith in Christ and participation in a Christian community. There was something present in their lives that I desired for my life. Eventually, I came to Christ.

Let us dwell on the phrase, “something present in their lives that I desired.” When I teach on the “Four Loves” (there are more than four, but Lewis made famous “the Four Loves”), I am always careful to note that, while Eros is used for sexual love, its Greek meaning is broader and deeper than merely sex. “Eros” is an evoked love. Something in the beloved draws us out of ourselves with a desire to be in community with it. Eros is a response to beauty.

I can eros a person, a house, a painting, a social entity, a community, etc. The beauty of the thing loved draws the lover into the relationship with the beloved. Do you remember my mentioning Francis Schaeffer’s “The God Who Is There”? Shortly after reading Schaeffer’s book, I read Edith Schaeffer’s “L’Abri,” the story of their life and ministry in Switzerland. Believe me, I was motivated to read the rest of Schaeffer’s works more by his wife’s book, and the loveliness of the life and ministry they created in Huémoz, than by Schaeffer’s books, which can be hard to read. Schaeffer is known for his apologetics, but people forget the attractiveness of the place he created in Switzerland.

The point is simple: If Christians wish to attract other Christians to their faith, then the first thing we must do is show them by our lives and relationships that Christianity is a beautiful thing that will bring them happiness, wholeness, and pleasure. We must create little communities of beauty where people can find forgiveness, healing, and wholeness for their lives. That is precisely what I saw at what we knew as “The Friday Night Bible Study.”

The point is simple: If Christians wish to attract other Christians to their faith, then the first thing we must do is show them by our lives and relationships that Christianity is a beautiful thing that will bring them happiness, wholeness, and pleasure. We must create little communities of beauty where people can find forgiveness, healing, and wholeness for their lives. That is precisely what I saw at what we knew as “The Friday Night Bible Study.”

Balancing “Show” with “Go”

Evangelical Christians know all about the Great Commission:

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely, I am with you always, to the very end of the age. (Matthew 28:18-20).

Just as foundational for the church and discipleship is the description of the first church in Acts, where it is recorded:

They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, the breaking of bread, and prayer. Everyone was filled with awe at the many wonders and signs performed by the apostles. All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who needed them. Every day, they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts, praising God and enjoying the people’s favor. And the Lord added to their number daily those being saved (Acts 2:41-48).

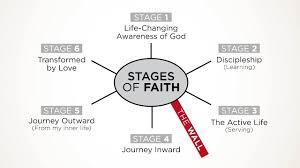

While the apostles’ teaching formed the intellectual basis for the little community, it was also characterized by community, table fellowship, and prayer, and the church’s generosity attracted everyone. The table fellowship and hospitality of the early church were just as crucial as its proclamation for the growth of the early church. When people saw the beauty of the first Christians’ fellowship, community, faith, and morals, they desired to join to experience the same joy. “Show” was as important as “Go” in the early church.[2]

A Vision of the End

People are motivated by love to seek the ends they choose; therefore, people need a vision for the end of life they desire. This week in my daily devotional, I was reminded that nothing is more important than falling in love. Furthermore, the most important love we can have is a love for God. As one author put it,

What you are in love with, what seizes your imagination, will affect everything. It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning, what you will do with your evenings, how you will spend your weekends, what you will read, whom you will know, what breaks your heart, and what amazes you with joy and gratitude. Fall in love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.” [3]

Many times I’ve told a story from my early Christian life. The men of our Bible study were playing touch football with the senior high from our church. The game was over, and I watched one of my friends holding hands with his wife, walking off the field. I was suddenly captured by the notion that that was exactly what I wanted my marriage to look like. Notice I hadn’t attended a seminar where a pastor or psychologist articulated the “seven secrets of a successful marriage.” I just looked and saw—and what I saw was beautiful.

In the Revelation, the apostle John gives us a vision of beauty when he describes the church as a beautiful bride or a city made of jewels and gold descending from heaven (Revelation 21:1-21). The idea is that faith in Christ and his Church is so attractive that it’s like the most beautiful bride you’ve ever seen or the most beautiful city you’ve ever imagined. This vision of a bride and a city was intended to motivate the early church to keep on in the face of persecution because of the attractiveness of the end for which they were striving. They were to show the people of the decaying Roman Empire a better, healthier, and more beautiful way of life.

The Final Judgement

In Matthew, near the end of his life, Jesus speaks of the end of times. He reveals himself as the judge of the Earth who will separate the sheep from the goats. The separation will be strictly based on how Christ was treated in the face of the victims of history:

Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the world’s creation. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me’ (Matthew 25:34-36).

How an “Ethics of Beauty” deals with this passage is important, and it is a position that illuminates the entirety of The Ethics of Beauty and its underlying meaning and purpose: The sacrifice of Christ on the Cross was not only a juridical action of God/Man dying for the sins of the world; it was also the most beautiful act of human history and an act that reveals the true nature of beauty, for sacrificial love is the most beautiful action of all. [4]

As Christians embody the beauty of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, there are many ways in which we act to reveal that beauty to the world. In addition to mission work, philanthropy, doing a good job in our ordinary lives in the world, serving other people, and taking care of our families, we also reveal the beauty of Christ when we pray, meditate, and live out the wisdom and love of God.[5]

Beauty in the Season of Pentecost

Christians best demonstrate the beauty of Christ when we take care of all of our responsibilities, from the smallest to the greatest, by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, which is, after all, the wisdom and love of God with us. There is a certain unpredictability about how the Spirit will lead us from time to time and in situation after situation. Love must be wise, but it really doesn’t have many rules. Instead, love adapts itself to the needs of those being loved. [6] Pattisis puts it this way:

When the Holy Spirit is moving, life becomes unpredictable…. It becomes fractal, and more than fractal; that is, fractals are a part of nature, but in the Spirit, we enter the realm of the supernatural. Each of the excellent ways of ministering to Christ in the least these of is present within all other ways.[7]

Here, we have an excellent statement of the freedom of the Spirit to move, which will create harmony and healing in human relationships. We are not mere automatons but people created in God’s image and being conformed to God’s image in Christ.

The Church as a Reflection and Symbol of Divine Love

Without in any way denigrating the activities of para-church and other organizations, the primary vehicle in which God intends to evangelize the world is the church. In the church, the world is to see the beauty of the Triune God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, reflected in the world. When the church fails to be that community of love, a beautiful thing set among the nations, it fails to disciple the nations. More than once in my pastoral career, I’ve had the opportunity to watch a very effective church destroy its effectiveness amid church conflict. I often tell my wife, “People are not attracted to a church that’s unhappy or arguing.” Everything the church does, from its worship to its fellowship to its teaching and other ministries, should be carefully constructed to reflect not just the truth of the gospel but its beauty. When we go astray—and all people and all churches do go astray—we confess what we have done, return to fellowship with God, and go forward. Not only is God’s original intention beautiful, but what God does with our brokenness and flawed beauty is lovely as well.

Copyright 2025, G. Christopher Scruggs, All Rights Reserved

[1] Tomothy Pattisis, The Ethics of Beauty (Maryville, MO: St. Nicholas Press, 2020).

[2] Id, 522.

[3] Pedro Aruppe, quoted in Peter Scazzero, Emotionally Healthy Relationships Day By Day (Grand Rapids, MI, Zondervan, 2017), 42.

[4] The Ethics of Beauty, 536-539.

[5] Id, 545ff.

[6] Id, 554ff.

[7] Id, 551.